The Mississippi Freedom Movement remains one of the heroic stories of twentieth century U.S. history. Students and faculty from Brown University and Tougaloo College conducted research in the Tougaloo College Archives to further explore this story. The documents presented here do not tell the whole story of the Civil Rights Movement, or even of Mississippi's role in what activists of the time called the Freedom Movement, but rather present one view available from the Tougaloo College Archives.

For background on the importance of Tougaloo College, please see:

Tougaloo College: Center of the Mississippi Freedom Movement, Ernest Limbo, Associate Professor, History, Tougaloo College.

This web site contains a searchable database of the documents chosen by the student researchers and the essays they wrote about groups of documents. You can explore the available documents by starting with the document cluster essays on the right or you can simply search the database. Either way you will learn about the obstacles faced by people who struggled to win equal rights for African Americans.

Brown-Tougaloo Exchange

Freedom's Martyr: Medgar Evers: Medgar Evers, one

of the first martyrs of the Freedom Movement, was born near Decatur,

Mississippi, on July 25, 1925, to James and Jessie Evers. Medgar left

high

school in the 10th grade to join the army and fight in World War II.

After serving as a sergeant in Europe, Evers enrolled in Alcorn

Agricultural and Mechanical School. [more...]

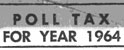

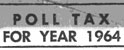

Voter Registration/Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party: The

Tougaloo College Archives provide rich resources for studying the struggle

to register African Americans to vote in Mississippi. A wealth of

documents tell the story of how a determined group of people from

Mississippi and from outside the state, both black and non-black, and of

all ages transformed the fundamental political structure of Mississippi

through grassroots organizing and through direct public challenges to a

system founded on, and governed by, the belief and practice of white

supremacy. [more...]

Voter Registration/Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party: The

Tougaloo College Archives provide rich resources for studying the struggle

to register African Americans to vote in Mississippi. A wealth of

documents tell the story of how a determined group of people from

Mississippi and from outside the state, both black and non-black, and of

all ages transformed the fundamental political structure of Mississippi

through grassroots organizing and through direct public challenges to a

system founded on, and governed by, the belief and practice of white

supremacy. [more...]

White Resistance: the Citizens Council and the Sovereignty

Commission: White citizens in Mississippi reacted to the Freedom

Movement with legislative initiatives, state funded organizations, and

private groups all designed to maintain racial inequality and prevent

blacks from voting. As the Freedom Movement activists looked to the

federal government, beginning with the Brown v. Board of Education case in

1954 that ordered the desegregation of public schools, whites in

Mississippi used the language of state's rights versus the federal

government to argue for the continuation of segregation. Many of the

initiatives first tried in Mississippi spread to neighboring Southern

states. [more...]

White Resistance: the Citizens Council and the Sovereignty

Commission: White citizens in Mississippi reacted to the Freedom

Movement with legislative initiatives, state funded organizations, and

private groups all designed to maintain racial inequality and prevent

blacks from voting. As the Freedom Movement activists looked to the

federal government, beginning with the Brown v. Board of Education case in

1954 that ordered the desegregation of public schools, whites in

Mississippi used the language of state's rights versus the federal

government to argue for the continuation of segregation. Many of the

initiatives first tried in Mississippi spread to neighboring Southern

states. [more...]

Reports from the Field: The Writings of Annie Rankin: Annie

Rankin, born in Harrison County, Mississippi in 1933, became active in the

Freedom Movement in 1964 when she attempted to integrate a lunch counter

in Natchez, Mississippi. Ms. Rankin stayed active in Movement work

through the 1960s. Her lively correspondence with her "freedom friends"

in the North gives a moving glimpse into the grassroots work on which the Freedom Movement was built. [more...]

Reports from the Field: The Writings of Annie Rankin: Annie

Rankin, born in Harrison County, Mississippi in 1933, became active in the

Freedom Movement in 1964 when she attempted to integrate a lunch counter

in Natchez, Mississippi. Ms. Rankin stayed active in Movement work

through the 1960s. Her lively correspondence with her "freedom friends"

in the North gives a moving glimpse into the grassroots work on which the Freedom Movement was built. [more...]

Black Power and the Republic of New Africa: Many of the

activists who worked in the Freedom Movement in Mississippi became

founders and participants in the Black Power movement, with Stockley

Carmichael (of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee -- SNCC)

giving the new movement its name during the Meredith Mississippi Freedom

March in the summer of 1966. At the pinnacle of the Black Power Movement

in the late 1960s, brothers Milton and Richard Henry, (acquaintances of

Malcolm X who renamed themselves Gaidi Obadele and Imari Abubakari

Obadele, respectively) assembled a group of 500 militant black

nationalists in Detroit, Michigan to discuss the creation of a black

nation within the United States. [more...]

founders and participants in the Black Power movement, with Stockley

Carmichael (of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee -- SNCC)

giving the new movement its name during the Meredith Mississippi Freedom

March in the summer of 1966. At the pinnacle of the Black Power Movement

in the late 1960s, brothers Milton and Richard Henry, (acquaintances of

Malcolm X who renamed themselves Gaidi Obadele and Imari Abubakari

Obadele, respectively) assembled a group of 500 militant black

nationalists in Detroit, Michigan to discuss the creation of a black

nation within the United States. [more...]

Economic Freedom: Children's Development Group of Mississippi:

Activism in Mississippi began in direct protest (the Freedom Rides and

lunch counter sit-ins) and Voter Registration drives but, by 1965,

organizers also turned their attention to economic and social welfare

issues. At first, SNCC workers in particular were skeptical that

President Lyndon Johnson's new War on Poverty programs would undermine

grassroots Freedom Movement power through financial and federal control.

But, in the summer of 1965, SNCC, along with northern white sympathizers,

applied for federal Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) funds to run a

series of Head Start programs for pre-school children under the auspices

of the newly formed Child Development Group of Mississippi (CDGM).[more...]

Economic Freedom: Children's Development Group of Mississippi:

Activism in Mississippi began in direct protest (the Freedom Rides and

lunch counter sit-ins) and Voter Registration drives but, by 1965,

organizers also turned their attention to economic and social welfare

issues. At first, SNCC workers in particular were skeptical that

President Lyndon Johnson's new War on Poverty programs would undermine

grassroots Freedom Movement power through financial and federal control.

But, in the summer of 1965, SNCC, along with northern white sympathizers,

applied for federal Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) funds to run a

series of Head Start programs for pre-school children under the auspices

of the newly formed Child Development Group of Mississippi (CDGM).[more...]