Reports from the Field: The Writings of Annie Rankin

Annie Rankin, born in Harrison County, Mississippi in 1933, became active in the Freedom Movement in 1964 when she attempted to integrate a lunch counter in Natchez, Mississippi. Ms. Rankin stayed active in Movement work through the 1960s. Her lively correspondence with her "freedom friends" in the North gives a moving glimpse into the grassroots work on which the Freedom Movement was built. Ms. Rankin's own self-conscious intellectual history, combined with her ability to express her ideas, help us trace the Movement from the sit-ins, through Voter Registration, to economic activities, Black Power ideas, anti-Vietnam War protests, and the Poor People's Campaign.

A Harrison County Mississippi native, Annie James Rankin was born to Mr. and Mrs.

William James on March 1, 1933. Somehow Mrs. Rankin was separated from her parents, and

adopted. She joined the Freedom Movement in 1964, "when things was really rough" as she

and others attempted to integrate a Sterling "ten cent store" in Natchez, Mississippi.

During the sit in, customers and store clerks threw cups and saucers at her and she was

verbally abused and harassed. In a letter to Northern friends, Ms. Rankin explains how

to conduct an effective sit-in. (#72).

After that first sit-in, Ms. Rankin became one of the most visible activists in the area

and lost her job after registering to vote. Mrs. Rankin filed a lawsuit against her

employer for firing her without proper cause. While she knew that the odds were against

her, she followed through with the case. When the first case was dismissed, she sued

again. Ms. Rankin also participated in the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party

challenge at the Democratic Party Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

Mrs. Rankin's next project led her to a jail cell. She participated in the March on Washington in June 1965 and was jailed for seven days. While in jail, Mrs. Rankin ate only two of the seven days because she refused food to ensure that two elderly women in her cell had enough to eat. She also refused to be released from jail until her two new friends were released with her. Ms. Rankin returned home to continue her activism. Her later letters dealt with the violence which remained part of the lives of African Americans long after the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed. (#71). She also wrote and spoke out about her opposition to the war in Vietnam and how she fought to keep young black men from being drafted. (#63) Ms. Rankin admired Stokely Carmichael and believed in the Black Power philosophy he expounded. Her interest in Black Power helps us understand the influence that ideology had over the grassroots activists and remember that not all Black Power advocates were young men. (#67).

In her handwritten autobiography (available in the Tougaloo College Archives but not included on this site), Ms. Rankin writes in detail about her experience driving a covered wagon pulled by mules to the Poor People's March on Washington in 1968. During her trip, she mourned the deaths of Robert Kennedy and the Reverend Martin Luther King, in addition to surviving violent attacks. When asked if the trip had been rough, Ms. Rankin replied, "I have always had it hard and I can take it. You see I am not one of those kind who will send you and I sit back. I don't send you, I lead you."

As part of the rally in Washington, Ms. Rankin spoke to the crowd:

I did not come here for the sweet name I would have. I did no(t) come here just to be seen but to help our race overcome. I did not come here to say what I didn't mean and mean what I didn't say. But I came here to say what I mean and meanwhat I say. I came to speak not only for my self but for the many poor people back in the Mississippi Valleys where I have lived for all my life and not just for one race but for all poor people regardless to race or creed. Poor people is my motto because I am poor . . . I am for justice and the only way it will happen we have got to get together. I am still fighting for freedom . . .

Related Documents

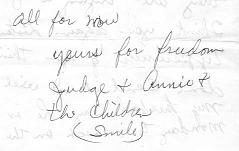

Letter,

Annie Rankin, 17 October 1967

Letter,

Annie Rankin, 12 August 1967

Speech,

Annie Rankin

Letter,

Annie Rankin, 25 May 1965