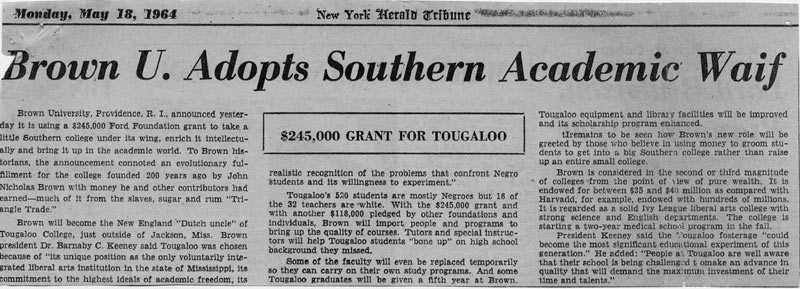

In May of 1964, on the tenth anniversary of Brown v. the Board of Education, the New York Herald-Tribune ran a story celebrating the beginning of the new Ford Foundation-funded cooperative relationship between Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, and Tougaloo College outside of Jackson, Mississippi, headlined, "Brown U. Adopts Southern Academic Waif." While Brown administrators were angry at what they saw as "particularly offensive . . . snide hogwash," the story was reported all over the country in a more positive light, quoting Brown President Barnaby C. Keeney saying that "this could be the most significant educational experiment of this generation." The deftly timed press release brought the cooperative program widespread attention, praising Brown's commitment to take on a significant role in the planning and operation of Tougaloo. However, the foundation of the program, and Brown's involvement with Tougaloo, had been growing for the previous year, as Keeney, members of the Tougaloo Board of Trustees (many of whom lived or worked in Rhode Island), and the Ford Foundation worked out the details of the program.

In May of 1964, on the tenth anniversary of Brown v. the Board of Education, the New York Herald-Tribune ran a story celebrating the beginning of the new Ford Foundation-funded cooperative relationship between Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, and Tougaloo College outside of Jackson, Mississippi, headlined, "Brown U. Adopts Southern Academic Waif." While Brown administrators were angry at what they saw as "particularly offensive . . . snide hogwash," the story was reported all over the country in a more positive light, quoting Brown President Barnaby C. Keeney saying that "this could be the most significant educational experiment of this generation." The deftly timed press release brought the cooperative program widespread attention, praising Brown's commitment to take on a significant role in the planning and operation of Tougaloo. However, the foundation of the program, and Brown's involvement with Tougaloo, had been growing for the previous year, as Keeney, members of the Tougaloo Board of Trustees (many of whom lived or worked in Rhode Island), and the Ford Foundation worked out the details of the program.

Unbeknownst to him, one of those "details" was the removal of Tougaloo President A. Daniel Beittel. Beittel, who came to Tougaloo from Beloit College in 1960, was popular with students, and was supportive, and even sometimes involved in, the Mississippi Freedom Movement. At Jackson's first sit-in, Beittel came to support and help ensure the safety of his students. To students, he represented hope for change and the future. To supportive religious leaders, he was a man of courage who would not bend to the pressures of Jim Crow Mississippi. To White Citizens' Councils, he represented a threat, part of an "international Communist Conspiracy." To Brown, the Tougaloo Trustees, and the Ford Foundation, he was obsolete, and a barrier to Tougaloo's becoming a "first-rate Liberal Arts College." As he turned in his letter of resignation on September 1, 1964, he presented himself as none of these -- simply an administrator trying to do the best he could. His resignation, a victory to some and a tragedy to others, nevertheless marked a crucial historical moment at start of the Brown-Tougaloo Cooperative Exchange, and great changes for Tougaloo and Mississippi.

After examing the scattered records left at Brown and Tougaloo, it is impossible to know for sure exactly why Beittel was fired and by whom. The only published speculation of the event comes to us from historian John Dittmer (a faculty member at both Brown and Tougaloo), in his book, Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (University of Illinois Press, 1994). Dittmer argued that Beittel was fired at the request of Brown University. But although the records are unclear, the rumors that surrounded his resignation persist, and investigation offers us both an interesting lesson on interpreting historical documents, and insight into the politics of the Mississippi Freedom Movement, white liberalism, white supremacy, money, and education out of which the Brown Tougaloo Cooperative Program emerged.

So, who fired Dan Beittel?

In 1956, the Mississippi government established the State Sovereignty Commission in response to federal desegregation orders. The mandate of the Commission (mostly run, according to Dittmer, with and by White Citizens' Councils) was to support institutionalized segregation and racism in Mississippi. The tax-payer supported Commission gathered information on Civil Rights Movements, intimidated individuals and supporters of those movements, and attempted to become "a public relations machine," spreading disinformation about movements and positive publicity about Mississippi. Good sources on the Sovereignty Commission are Yasuhiro Katairi's book The Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission (University of Mississippi Press, 1997) and the essay on this website.

When students and organizers at Tougaloo College began moving off campus to take part in marches, actions, and civil disobedience in Jackson, and other places, in 1962 and 1963, the Sovereignty Commission noticed. The Commission focused on Beittel and Reverend Ed King (who they named as "collaborators" with "the southern arm of the communist conspiracy") as influences responsible for making Tougaloo "more of a school for agitation than a school for education." (#10172) Collecting information from their "white informant at Tougaloo," internal documents show that in early April 1964, the Sovereignty Commission found an opportunity to strike. Wesley Hotchkiss, a Tougaloo Trustee, described as a "very political man," was said to be lobbying the board of trustees to replace Beittel. The Commission's strategy was to "Offer a trade with Mr. Hotchkiss and those in authority. We will suggest that Dr. Beittel and Ed King be removed from Tougaloo and in return we can pledge that the legislature will take no action on revocation of the charter." At the time the State Legislature had, in fact, been threatening to revoke Tougaloo's charter. {Memo, Director, Sovereignty Commission re: Tougaloo College, 13 April 1964, Director's File, Sovereignty Commission Papers, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Document Number SCR ID 1-84-0-8-1-1-1.}

On April 17, the Sovereignty Commission sent a letter to Wesley Hotchkiss offering that trade. While Hotchkiss, in other correspondence, denied that the letter and the Commission had any influence on the decision to fire Beittel, it is suspicious that the Sovereignty Commission would have known the inner workings of the Board of Trustees at a time when it was firmly at odds with Tougaloo College and its administration. And though the decision to replace Beittel came clearly in early April 1964, before the Sovereignty Commission's letter was sent, the effect of the commission's intimidation can be seen clearly in another Trustee's (Bob Wilder) April 8 letter to Keeney about finding a new President:

Frankly I feel we must run like the Devil himself to sign our new man up by June 30th at the very latest, and May 30th, if humanly possible in order to avoid a one year holding operation. The times are too critical, the need is too great; the State of Mississippi is too militant for us to give them the impression we are hesitating.

When it was announced that Beittel would be removed, three religious leaders, including Rev. Bernard Law (now former Cardinal Law), sent a letter of support for Beittel, which argued to the Trustees that "Tougaloo is finally surrendering to the intimidation!" In the Brown archives, that letter is accompanied by a note to President Keeney: "FYI: Tougaloo's Trustees know these are friends of Beittel's. No problem."

The Tougaloo Trustees replied to those religious leaders by saying that "Any attempt to infer that Dan Beittel's relationship to the civil rights movement has had any affect on the decision of the Board is not the truth." (#10175) Wesley Hotchkiss continued, saying that the Sovereignty Commission "complicated" the retirement, and acknowledged that it looked bad, saying it "risked a rumor war both from the Sovereignty Commission and from the Beittels." In the end, he said that "their visit is of no consequence whatever to the actions of our Board." (#10176)

Eyrle Johnston, the Director of the Sovereignty Commission, himself told Beittel that "I had nothing to do with your firing, but was delighted to hear of it, and if there was a way I could have brought it about I would have." However, it is unclear who is telling the truth, or the complete truth, in all of these documents, as earlier the Sovereignty Commission had claimed a success. {Memo, Erle Johnston re: Dr. A.D. Beittel, 31 December 1964, Director's File, Sovereignty Commission Papers, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Document Number SCR ID 1-84-0-14-1-1-1.} One thing is clear: the actions and pressure of the Sovereignty Commission and Mississippi's white supremacists were at least considered by the Tougaloo Trustees (and Brown administrators). The Commission's opinion was most likely weighed in with "other" factors, like Hotchkiss' complaints that "Dan has shown no comprehension of the importance of the Brown Tougaloo academic program nor has he known how to take responsibility for dealing with foundations and major donors." (#10176) Which leads us to our next two subjects.

Historian John Dittmer found Brown University, and in particular former CIA agent Keeney, the culprits ultimately responsible for Beittel's firing. Beittel actually claimed he was told, by Chair of the Tougaloo Trustees Bob Wilder that he "was to be replaced at the urgent request of Brown University." In response, Keeney wrote Beittel had:

Gained the impression that Brown had insisted upon his retirement. I wrote him denying this and telling him that we had been told before we even entered the program that he was going to retire. This must be handled very carefully because it would be disastrous if the word got around that Brown was interfering in the internal affairs of Tougaloo. (#10177)

This was nonsense, of course. In that very letter, Keeney wrote his opinions and recommendations about candidates to replace Beittel. Weeks earlier Keeney had sent another letter to Wilder specifying the "characteristics," that the selection committee should consider when selecting a new president. To Beittel, he wrote that he had known Beittel was to be replaced "last fall." He regarded the suggestions Beittel made "extremely unfortunate," and wished to "deny [them] emphatically . . . . My only interest is that the College operate effectively. "

Beittel also wrote to Hotchkiss, saying that in a conversation on April 1, "You indicated that Brown University would not continue our cooperative relationship unless I am replaced, that without Brown University the Ford Foundation will provide no support, and without Ford support other foundations will not respond, and without foundation support the future of Tougaloo College is very uncertain." Hotchkiss, like Wilder and Keeney, bent the truth in his response. He said that "the only contacts I have had with Brown were with representatives of their development office who were advising the Tougaloo Board on our development program," despite the fact that he had corresponded with Brown President Keeney. Hotchkiss continued to maintain that Brown had not requested the resignation, but that "the trustees are convinced that you have no comprehension of, or interest in, the proposed relationships with Brown University and, for this reason, the trustees are suggesting that you take advantage of your opportunity to retire." (#10079)

A newer member of the Tougaloo Board, Merle Miller, wrote to Hotchkiss that "Beittel's reaction could have been written in advance by any competent playwright." He felt that Beittel was dramatizing the situation, and he had been convinced, by the lobbying of Hotchkiss and others, to vote to force Beittel to resign, as he felt "that identification with Brown University is the only salvation for Tougaloo and that anything that interferes with that identification must go in the interest of Tougaloo. If Dr. Beittel . . . has placed Tougaloo in a position where Tougaloo cannot take advantage of the plan of cooperation with Brown, then Dr. Beittel . . . must go . . . . We cannot permit anything to stand in the way of our future development and we must therefore obtain the service of a President who can take advantage of the offer of Brown University."

Finally, the Trustees claim that the decision to ask for Beittel's "retirement" came in January at the Board of Trustees Meeting, and he accepted then, and only later changed his mind. However, Beittel never acknowledged this event, and there is no record of it in the minutes of the Trustees meeting. In fact, in his resignation letter, Beittel claimed that if the decision to make him retire came from the January meeting, it was a special meeting of less than half of the Board, and the decision was not presented to him until April. It is unknown whether or not Brown University was involved in these early discussions among Hotchkiss, Wilder, and others. But Brown administrators were involved later on, and it does not take a stretch of the imagination to consider that, in the early stages of planning the cooperative exchange program between representatives of the Board, Brown, and the Ford Foundation, the issue of Tougaloo's administration came up. In fact, some Board members and representatives of the Ford Foundation actually shared complaints about Tougaloo's President early on. Those complaints lead us to our next suspect.

The role of the Ford Foundation in the formation of the Brown Tougaloo Cooperative Exchange is a nebulous one. As Keeney and other Brown administrators began to plan the grant application with Tougaloo Trustees, they were in constant contact with representatives of the Ford Foundation. In particular, the Ford Foundation's Education Division Program Director Frank Bowles and Keeney had a very friendly relationship. On April 30, a few days after Beittel publicly announced his "retirement," Keeney received a handwritten note from Bowles, headed, "Dear Barney,"

The Fund Board, Monday afternoon, approved 240,000 for Tougaloo, without strings. To be administered by Presidents of Brown and Touglaoo or their duly authorized deputy. Have fun -- Frank.

While it may seem their relations were cordial enough, the process of wooing the Ford Foundation, which resulted in millions of dollars over the next few years, did not start off so well. Exactly what happened is not clear from the documents, but it appears as if President Beittel may unwittingly have angered the Ford Foundation. Keeney scolded him on March 9:

I have learned that presidents of other colleges have made proposals to the Ford Foundation for support of some of the enterprises specifically mentioned in the application to the Ford Foundation which we prepared on your behalf. This has, of course, confused the executives of the Ford Foundation and has also irritated them. It has, moreover, obscured what I had thought was a relationship in this enterprise between Brown and Tougaloo.

The apparent cause of Keeney's and Ford's ire, Beittel believed, lay in a visit the Beittel made to Franklin and Marshall College, and a discussion he had with them about a post-secondary program similar to one in the Brown-Tougaloo grant. Franklin and Marshall College submitted a grant proposal to the Ford Foundation listing Tougaloo College as part of the program. Beittel claimed he had no knowledge of the proposal and Keeney wrote, "I believe you have been more sinned against than sinning. I shall clear it up with Frank Bowles when I see him next." (#10171)

When talking to Tougaloo Trustees, however, Keeney told a different story. On March 9, Keeney wrote a letter to Lawrence Durgin, a Tougaloo Trustee. In it, he said "The Chairman of the Board should write Frank Bowles as soon as possible that efforts are being made to secure a new president. They will not do much, if anything, until they have this assurance . . . I am still very much steamed up about the place and hope that we can help." If it were not for the Trustees' insistence that they told Beittel to retire in January, this would be enough proof, a "smoking gun," to show that a collaboration between the Ford Foundation and Brown was responsible for firing Beittel. There is no record of this in the minutes; however, there may be some truth to this story. Which leads us to our final suspect.

On April 10 1964, Wesley Hotchkiss sent a note to Chairman Bob Wilder, explaining that Beittel was resisting the request to retire on September 1. Hotchkiss said that Beittel blamed Brown University pressure for his firing and wrote that "we must make clear to Dr. Beittel that the decision of the Board that he should retire is our own decision and not one taken in response to any pressure by Brown." {Hotchkiss to Wilder, 10 April 1964 - letter not available}

In this letter we are shown the clearest timeline, and we have reason to believe that it is the most accurate, as it is a confidential note between two Trustees. At the "special" January meeting, Hotchkiss said, the culmination of much dissatisfaction with the administration led to the formation of a special committee to search for a new president, and they spoke with Beittel about the possibility of retiring. Hotchkiss said that "later on" there was another meeting (on March 25, well after Keeney wrote Durgin) that set a firm date of September 1, 1964 for Beittel's resignation, and began to discuss searching for a new President.

Hotchkiss listed several Beittel's faults and said that he was in favor of retirement, "completely independent of the Brown University offers of cooperation." The lack of adequate response to the Brown offer, Hotchkiss said, was merely the icing on the cake:

I personally have no reservations about the motives of Brown and I am satisfied that Brown intends no infringement upon the autonomy of Tougaloo College, but as a responsible Trustee I feel we do Tougaloo a great disservice not to take advantage of the offer of Brown to be of help. . . I feel the survival of Tougaloo will depend [on it]. {Hotchkiss to Wilder, 10 April 1964 - letter not available}

It is unclear how many of the Board members present at the January and March meetings (many of whom were new and inexperienced, according to Miller) felt the same way. It is also unclear exactly what happened at the January meeting. Perhaps the March 25 meeting was merely, as Keeney insisted it was, a response to Brown's requests to hurry the "retirement" process along. Or, perhaps the pressure from outside sources began before early March. Or, perhaps nothing happened at the January meeting. It is impossible to know for sure, with the documents we have.

Reviewing the evidence, we are left to speculate. On one hand, we have the Trustees' story, that they had been planning to fire Beittel since the fall, and attempted to start the process gently in January, but by moving slowly and trying to let him down easily, they opened themselves up to rumors and speculation about their motives. On the other hand, we have evidence that Beittel was despised by the racist Sovereignty Commission, which had ties to the FBI, and informants and operatives in Tougaloo College, and possibly sympathizers elsewhere. We have Brown University, headed by a former CIA agent who left intelligence work to head a university and an organization that focused on raising money for the humanities from government and non-government sources. We have a University and Ford Foundation with at best a checkered past, with administrators who were church fellows and golf buddies with members of the Tougaloo Board. There could very easily be some truth in the rumors about foul play in Beittel's firing. The conspiracy theorist in all of us wants to read between the lines and connect the coincidences, and the rational thinker wants to see the simplest explanation. The truth is probably somewhere in between. But we may never know.

What we do know is that the firing of President A. Daniel Beittel marked the beginning of the Brown Tougaloo Cooperative Exchange, the beginning of a new era in the history of Tougaloo and Black Mississippi, and the end of what came before it. Whether his resignation was seen as a victory, an opportunity, or a tragedy, as student Elizabeth Sewell wrote in her poem "For A.D. Beittel," 1964 was "quite a year for heads falling."