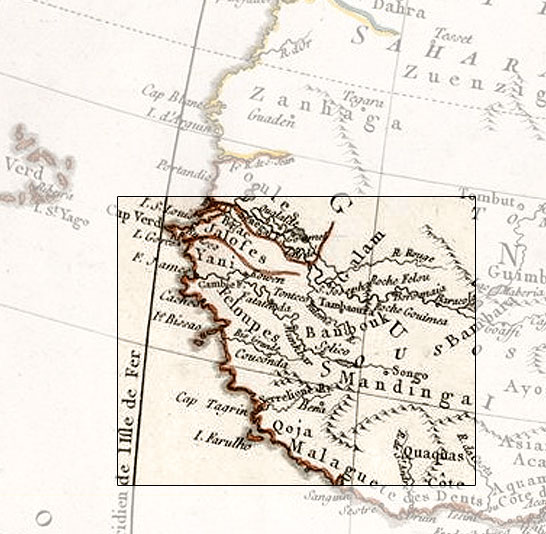

The Guinea Coast of Africa

The Sally's account book offers a meticulous record of economic transactions on the ship, describing the date of each purchase of an enslaved African and precisely what was traded for him or her. Unfortunately, it offers little information about his ship's exact whereabouts. It is unclear where the Sally first made landfall when it arrived in Africa on November 10, 1764, but by December it was at James Fort, the primary British "factory," or slave trading post, on the Upper Guinea coast, near the mouth of the Gambia River. The ship seems then to have proceeded south along the coast of what is today Guinea-Bissau, stopping briefly at the city of Bissau before anchoring somewhere near the mouth of the Grande River. This was Portuguese territory, supposedly off limits to ships from other countries, but there were a few British factories in the area and British slave ships often stopped there on the way down the coast.

Slave ships typically worked their way up and down a stretch of coastline. The Sally, in contrast, seems to have spent most of its time in one place, apparently the site of a small British factory. Judging from the account book, the Sally operated as a kind of rum dispensary, supplying passing slave ships with the rum they needed to conduct business on the coast and receiving in exchange manufactured goods like cloth, iron, and guns, which were in turn exchanged for supplies or captives. When food stocks ran low, the Sally's captain, Esek Hopkins, bartered with locals or dispatched one of the Sally's boats up the coast to Bolor, a rice-trading settlement on the Cacheu River.

Slaves slowly trickled in, usually one or two at a time, some purchased from local slave traders, others from passing slave ships. On several occasions, Hopkins dispatched a boat to "Jabe" – probably Geba, a trading center up the Geba River – to purchase small lots of captives. By the time the Sally finally embarked for the West Indies, in August 1765, Hopkins had acquired a total of 196 Africans, some of whom he then sold to other traders. Nineteen Africans had already died on the ship, and a twentieth was left for dead on the day the ship departed.

Map Details

Brion De La Tour, Louis Paris, 1775

American Museum of Natural History