Nastagio degli Onesti (V.8)

In a French manuscript illumination dating from the first quarter of the fifteenth century (unfortunately not available due to copyright reasons), the illuminator has taken several artistic liberties to render what appears to be a very polite, glossed over version the of story of Nastagio. Although the fleeing girl is very clearly described in the text as being nude, in this illumination she is fully dressed in robes of vivid blue. There is also no indication of the intestinal mauling she is about to receive, seeming instead to be losing only the hem of her dress. This conservative approach to the depiction of the body and violations of it is characteristic of much of the manuscript, often showing supposed lovers fully covered by bed sheets and seized by a puzzling lack of mutual interest, or highly unrealistic or censored versions of violence.

The visual strategy employed to depict the narrative creates a clear, unified image in which the two pivotal scenes of the story have been combined into one unbroken composition. The doomed souls are shown only once, roughly in the center, and at the left we observe Nastagio witnessing this scene of retribution for the first time. Watching the same scene from the other side are Nastagio again and his banquet guests, including the scornful object of his affections. We know that Nastagio is depicted twice because of the identical robes, head wrap and sword; we can distinguish his lady guest because she is the only female figure at the table, and she gives away her anxiety in her guilt- and fear-ridden expression.

The technique of repeating figures within the same pictorial frame in order to convey narration is used throughout the manuscript, but the story of Nastagio is one of the few that manages to go beyond repetition and to unify further the series of images by looking at one group of figures from two points of view. This implied multiple perspective was perhaps also an early experiment in the course of the development of illusory perspective. Without realizing fully the rigorous technique that was to soon become the central catalyst for the Italian High Renaissance, this illumination nevertheless attempts to exploit an intended effect of drawn three-dimensional space.

Dating from the last quarter of the fifteenth century, Jacopo da Sellaio's rendition of the story of Nastagio has drastically altered the representation opted for in the French manuscript described above. Instead of unifying the story in one picture, what we see is only the first scene of the story, in which Nastagio stumbles upon an enactment of the doomed souls' punishment. The motif of repeated figures is carried into this depiction, but in a very different way: the first Nastagio is contemplative with a downcast glance, and the second is actively involved in trying to protect the fleeing girl. It still creates an image that depicts successive and not simultaneous moments, but the moments shown occur much more closely together than those in the illuminated manuscript. An important consideration at this point, in order to help clarify the different priorities in representing this story, is the medium of each. The illumination is from a manuscript, whereas the Sellaio painting is on a panel, and was most likely at one point mounted on a cassone, or a free-standing chest, that was commonly presented as part of a wedding gift. It can be assumed, then, that this panel was only one of three or four parts that were each mounted on such a chest.

Botticelli, Nastagio degli Onesti [outgoing link to: Web Gallery of Art] Similarly, Sandro Botticelli created four panels portraying the Nastagio tale, for a cassone commissioned by Lorenzo de' Medici, three of which reside currently in the Prado in Madrid. The tale is here depicted with gruesome enthusiasm and frightening realism. The most renowned adaptation of the tale, this series was certainly influenced by previous interpretations and yet the originality of the work is unmistakable. The first of these four panels is presented to the left.

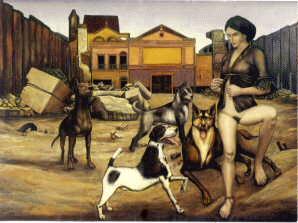

One notices a striking departure in style and intention in João Câmara's rendering of the tale of Nastagio, presented below (1991, oil on canvas):