The month of August, 1764, brought a flurry of activity, as the Sally was outfitted for Africa. Local craftsmen clambered over the ship, preparing canvas and rigging, sealing the hull, and installing tackle, including seven "swivel guns" – guns that could swivel outboard to defend the Sally against other ships and inboard when enslaved Africans were exercised on deck. Stores and provisions were laid in for the journey, including thousands of gallons of New England rum, which would be exchanged for enslaved Africans.

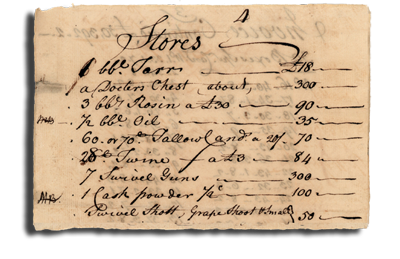

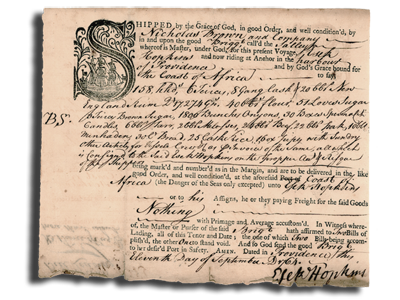

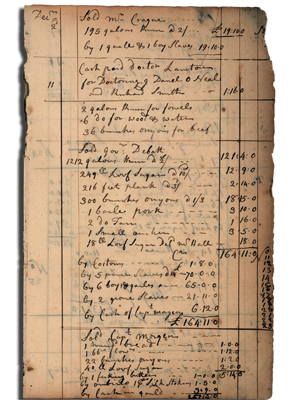

With crew aboard and cargo stowed, the Sally embarked for Africa on September 11, 1764. The ship carried a wide variety of goods, including thirty large boxes of whale oil candles manufactured in the Brown brothers' Providence candleworks, 1,800 bunches of onions, forty barrels of beef and pork, and hundreds of casks of New England rum -- 17,274 gallons in all. Many of the casks would leak during the transatlantic journey, the first of many financial setbacks on the journey.

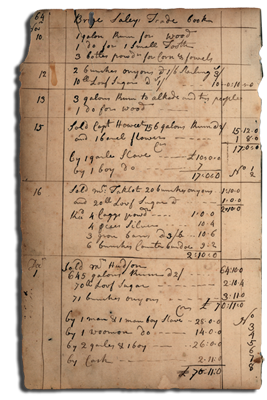

After a two-month passage, the Sally arrived in Africa in early November, 1764. It is unclear where the ship first made landfall. Captain Hopkins opened trade on November 10, exchanging two gallons of rum and a small quantity of powder for wood, corn, chickens, and a "small Tooth" — an elephant's tusk. On November 15, he purchased his first enslaved Africans, a boy and a girl, from the captain of another slave ship, in exchange for 156 gallons of rum and a barrel of flour.

By early December, the Sally had arrived at James Fort, the primary British slave "factory" on Africa's Windward Coast. Located fifteen miles from the mouth of the Gambia River, James Fort was the collection point for slaves coming down from the interior, and British and North American ships routinely stopped there to acquire provisions and slaves. On December 11, Hopkins purchased thirteen Africans from Governor Debatt, the British official who ran the fort, in exchange for 1,200 gallons of rum and sundry stores.

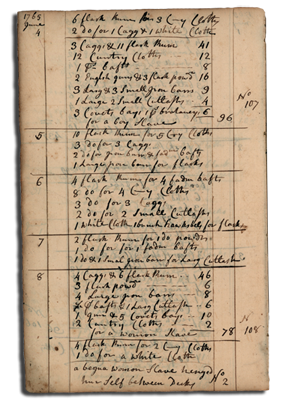

While most slave ships worked their way along the coast, the Sally appears to have remained largely in one place, apparently at a small British slave "factory" near the mouth of the River Grande, in what is today Guinea-Bissau. Hopkins traded rum with passing slave ships, acquiring manufactured goods like cloth, iron bars, and guns, which he then used to acquire slaves. On June 8, 1765, he purchased his 108th captive. That same day, an enslaved woman committed suicide. She was the second captive to die on the ship.

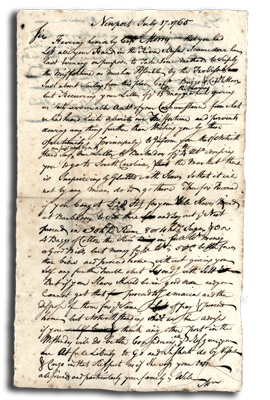

In June, 1765, after months with no news from the Sally, the Browns received reports that the ship and crew had been lost. Those rumors were contradicted on July 17, when a letter belatedly arrived from Hopkins, safe on the River Grande. Though Hopkins reported the loss of one crewman and substantial loss of his cargo through leakage, the Browns were elated. Your letter "Quite Aleviates our Misfortune," they wrote.

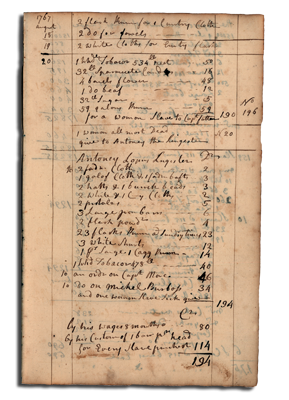

On August 20, 1765, more than nine months after his arrival on the African coast, Hopkins acquired his 196th and final captive. Nineteen Africans had already died on the ship. A twentieth captive, a "woman all Most dead," was left behind as a present for Anthony, the ship's "Linguister," or translator. At least twenty-one Africans had been sold to other slave traders on the coast, bringing the Sally's "cargo" to about 155 people.

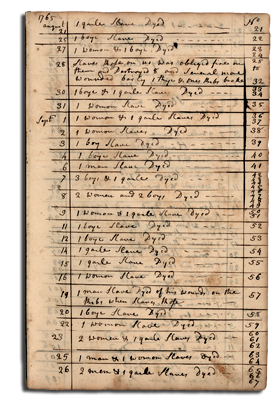

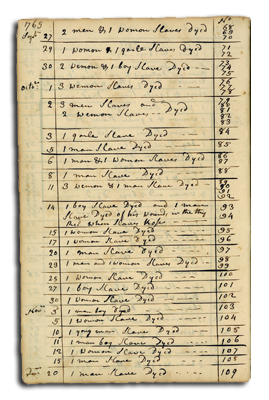

Four more Africans died in the first week of the Sally's return voyage. On August 28, desperate captives staged an insurrection, which Hopkins and the crew violently suppressed. Eight Africans died immediately, and two others later succumbed to their wounds. According to Hopkins, the captives were "so Desperited" after the failed insurrection that "Some Drowned them Selves Some Starved and Others Sickened & Dyed."

The Sally reached the West Indies in early October, 1765, after a transatlantic passage of about seven weeks. After a brief layover in Barbados, the ship proceeded to Antigua, where Hopkins wrote to the Browns, alerting them to the scope of the disaster. Sixty-eight Africans had perished during the passage, and twenty more died in the days immediately following the ship's arrival, bringing the death toll to 108. A 109th captive would later die en route to Providence.

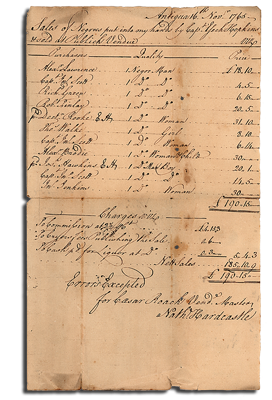

When they dispatched the Sally, the Brown brothers instructed Hopkins to return to Providence with four or five "likely lads" for the family's use. The rest of the Sally survivors were auctioned in Antigua. Sickly and emaciated, they commanded extremely low prices at auction. The last two dozen survivors were auctioned in Antigua on November 16, selling, in one case, for less than £5, scarcely a tenth of the value of a "prime slave."

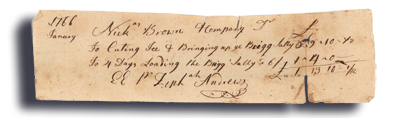

The Sally finally returned to Providence in the last days of December, 1765. Its cargo, a shipment of salt purchased at Turks Island, had been ruined by leakage, a final financial blow in a thoroughly disastrous voyage. Among the final accounts for the ship is a bill for nine shillings, ten pence, paid to a local laborer, Lepheniah Andrews, to chop away ice so that the ship could be brought up the Providence River.