Danzig -- Intellectual Life -- Danzig Academy (Danziger Gymnasium)

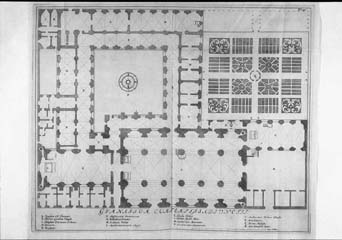

The Danzig Academy was founded in 1558 to train students of the new faith for the university. Its first home was the former Franciscan Monastery. Latin was the language of instruction, and humanistic training remained the basis for theological interests. Cicero and Demosthenes, Virgil, Horace, and Homer were studied for their rhetorical style and eloquence. The Academy boasted chairs in seven disciplines: theology (tied to the rectorship), law and history, physics and medicine, philosophy, rhetoric and poetry, Greek and oriental languages (Hebrew), and mathematics. Music was also studied and, as at universities, students were obliged to participate in public disputations and examinations. Throughout much of its history rhetorical skills were exercised in dramatic performances of Latin or German comedies. The academy retained its reputation for excellence into the 18th century.

The City Council called professors to their academic posts. Under the rectorship of Jacob Fabricius (1580-1629) the academy manifested distinct Calvinist sympathies, in harmony with those of the patrician Councillors. However, the majority of the population so opposed this tendency that one distinguished professor, Bartholomäus Keckermann, was attacked by a crowd and obliged to flee the academy disguised as a woman. Under the rectorship of Johannes Botsack (1631-1643) the academy returned to fold of the orthodox Lutherans. Indeed Aegidius Strauch (Rector 1670-1682) became one of the most vocal and most popular detractors of Calvinists, Catholics and Poles. With great popular support he challenged the authority of the Calvinist City Councillors and was subsequently removed by them from his post. Johann Georg Kulmus's first father-in-law, Tessin, was involved in trying to get Strauch released from prison (in Küstrin, Prussia as a Swedish spy). He did not return to Danzig after his release.

The rectorship remained controversial under Samuel Schelwig. The academic designs of Pietists (more reading of the bible, more attention to piety in daily life) made no inroads at the Danzig Academy under this leading German anti-pietist, the author of the well-known Itinerarium Antipietisticum, Das ist Kurtze Erzehlung einiger Dinge / so Trauff seiner / schon im vorigen 1694sten Jahre verrichtteten Reise / der Pietisten wegen / in Teutschland wahrgenommen / Auff Veranlassung zweyer Pasqvillen / nunmehr Durch offentlichen Druck gemein gemacht (1695). Indeed Schelwig (also pastor at St. Trinitatis) railed against Theodor Gehr in Königsberg (and others) for attempting such a curriculum. In general, anti-pietist sentiments in Danzig received vigorous support from this forceful personality.

[Bernhard Schulz. Das Danziger Akademische Gymnasium im Zeitalter der Aufklärung. In Zeitschrift des Westpreußischen Geschichtsvereins. 76 (1941) 5-102.]