Casey Shearer Memorial Award for Excellence in Creative Nonfiction, 1st Place

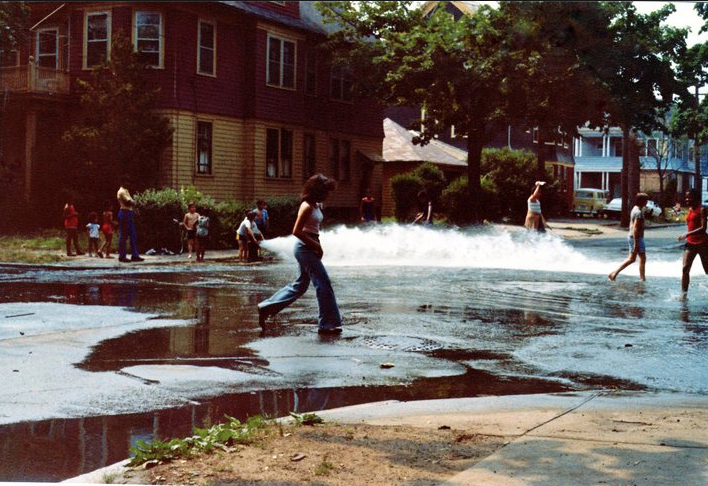

Flooding in the '80s, Olneyville

The River

The river, 18 miles long, scrawls a child's shaky letter "U" through the heart of Olneyville, running parallel to Manton Avenue then turning north to follow Valley Street out to the harbor. At its bend, it comes within feet of the chaotic traffic junction of Olneyville Square, where Plainfield, Hartford, Manton, Broadway, and Westminster streets converge.

The Woonasquatucket River flows into the Narragansett Bay flows into the Atlantic. The history of the area we call Olneyville today begins with the river. The Narragansett Indians were the first to settle there, building a trade center around the river and giving it its name, Algonquian for "As Far as the Salt Water Flows."

Local entrepreneurs became interested in the Woonasquatucket at the turn of the 19th century after the success of Samuel Slater's textile mill,built on the nearby Blackstone River in Pawtucket. Narrow and swift, the river was ideal for building dams and water wheels that could power the new paper and textile mills. These factories joined smaller ones built a few years before, such as Christopher Olney's woolen mill, which became the namesake of the town. Olney Ville was soon shortened to Olneyville.

The Mill

Immigrants of many backgrounds came to work in the mills. A new railroad juncture brought the Polish, German, Italian, and French Canadian to what had become an established English, Scottish, and Irish neighborhood. A yellowed image of Olneyville Square in a newspaper clipping from 1937 shows a bustling center of commerce that rivaled Providence's downtown. Newly waxed automobiles line the curb outside the shops. An electric trolley snakes up Manton Ave to the Atlantic Mill, the neighborhood's largest employer. Middle class families bustle about doing their weekend shopping at Grand Central Market, Kennedy Butter, and Sans Souci five and ten store. There is a line around the block for a matinee at the grand Olympia Theatre. DRUGS/CANDY/ FILMS/ SODA, the sign reads.

Rick Mancuso was born and raised on Barstow Street by Valley St. in Olneyville, where his mother was born and still lives. Like many of the neighbors, his family had emigrated from Italy in his grandparents' generation. He remembers the rotten smell of rubber that hung over the mills in the late Depression era, and the whistle that called the workers to the mill each morning at seven AM. Growing up as an only child under the tight grip of his mother, the river was a refuge and a companion. "The river," he says, "it's kind of in my blood, it's where I used to escape to be by myself."

The neighborhood kids called the falls across the park the Bare Ass Paradise. At twilight, teenage boys and a few adventurous girls would peel off their clothes and swim in the water. Rick peered at them from behind the grass, bound by fear of severe punishment from Mother not to touch the water, rife with industrial waste pollution. During the same time, he remembers hearing about a man who washed over the falls and raked his back open. Later, Rick found out that the man had died from the poison that got into his wound from the water.

Though damned and contaminated, the river was sacred to Rick. He watched in terror as his schoolmates shot bullfrogs with BB guns and caught snapping turtles with pitchforks thrust through their shells, once torturing one with cherry bombs on the baseball diamond behind the school. "It was a horrible thing," he said, "you see I developed compassion because I wanted to fight them all and say, 'Stop it, stop that.'"

Rick still lives near the river, and near his mother, who is 90 years old. In the stories he tells, he calls her "Mother," as if he were still very small and she very big. When I call him to arrange an interview about the neighborhood, he tells me I should talk to his mother. If I reach her, he asks, could I tell her to call him? She has been ignoring him, he said. I laugh nervously at the suggestion of my interference. They don't speak easily or often to one another, necessary words caught in the slow eddy of years.

The Flood

In 1954, salt water came up the bay and spilled into the streets. After three days of rain from Hurricane Carol, the Woonasquatucket's narrow sides opened in awesome swelling. Workers left the factories in boats. Rick Mancuso remembers seeing Valley Street Park underwater.

For the neighborhood as it was, the flood came at the beginning of the end. World War II had pushed textile giants, whose fortunes largely declined after the war, to the American South for cheaper manufacturing. In Olneyville, thousands of jobs were lost and never replaced, devastating the working class neighborhood. Houses wereboarded up as people moved out. In the 1950s, US Routes 6 and 10 merged to create a highway bypass of Olneyville, directing cars away from the Square and sucking its commercial lifeblood. In the following decades, the neighborhood became the site of property destructions, absentee landlordism, and crime. The river became a dumping ground for chemical and large solid debris.

The Frontier

In 1998, President Clinton named the Woonasquatucket River an American Heritage River, pledging government support to help the community clean up pollution and revitalize the waterfront. Today, community organizations and non-profits such as the Olneyville Homeowners Association, the Nickerson House, and the Olneyville Housing Corporation work actively to improve living standards, health, and job services in the neighborhood.

Despite the stabilizing changes, a feeling of frontier persists in Olneyville. Three hundred years after its settlement, there remains an unsteady promise of possibility for new residents. There is also the compelling appeal of "cheap, big, plentiful space," as Dan Schliefer, a member of the What Cheer? Brigade who has lived in Olneyville for eight years, puts it. "Cheap," "big," "plentiful"-these could be the words of pioneers at the frontier. The band practices at Building 16, one of many old factory or mill spaces turned artist studios. Where else, Dan points out, could the What Cheer? Brigade, a raucous 19-piece brass band, play without deafening neighbors?

In the 1990s, a few artist collectives moved into former mill buildings and warehouses, most prominently the legendary Fort Thunder collective near Eagle Square. The raucous culture of Fort Thunder, where artists' living spaces and studios also became the venue for noise rock shows and events like costumed wrestling matches, attracted more artists to the neighborhood. Today, too, some artists choose Olneyville overtly for its "wildness," Dan says, and the freedom to live with minimal consequences.

At the same time, a flood of Hispanic immigrants largely effected the repopulation of Olneyville. As several waves of immigrants from Guatemala, the Dominican Republic, and other parts of Central America arrived in Olneyville, the Hispanic population jumped from 34.9 percent in 1990 to 57.4 percent in 2012. Neighborhood associations such as the Olneyville Homeowner's Association (OHA) are comprised of mainly Hispanic residents who want to work to build the community. Alvaro Morales, who helped found OHA, remembers Olneyville as desolate and damaged when he first arrived from Guatemala in the 1980s. Homeownership, he argues, places the responsibility to control the neighborhood in the hands of residents and "that is how everything will change," he says.

Xander Marro, co-founder of the Dirt Palace, a women's art collective in Olneyville Square says that the different populations in the neighborhood are "brought together by everyone's shared sense of vulnerability, whether it is artists living illegally in warehouses [or] immigrants living without papers." The equation of the vulnerability of the artist population to that of the immigrant population is problematic, however. While the artist community is familiar with sudden evictions and displacements (this December, Building 16, a hub for artists in Olneyville, will be shut down to make way for new development), they are in no small part the catalyst for the neighborhood's gentrification, which continues to push up the price of rent for both populations.

Resurge

In 2010, Rick watched 1954 wash over him. He remembered being eleven years old then and seeing Valley Street Park blank with water. This time, it was the water from upstream that came down. Two monster rainstorms back-to-back flooded the neighborhood. In the basement of Cathedral Art jewelry factory, which sits near the river's crossing at Manton Avenue, a five-foot wall of water threatened to go over the cyanide-coated top of the jewelry plating tanks, almost causing an environmental catastrophe.

Three years after the 2010 flood, Dan is afraid that in the future, Olneyville will be swept away. "It is a fairly low-lying area," he says. "We saw it a couple of years ago," he tells me, "and with climate change there is every reason to think we'll see flooding again the next few years. If it seems doomed, people may give up on the neighborhood."

+++

A current is formed by waves that build to constancy. When Rick Mancuso was little, the neighborhood was mostly Italian; now it is mostly Hispanic. Since its founding, Olneyville has been home to periodic waves of immigrants: in Rick's day Western European, later Eastern European, now Central American. "In some ways, it is relatively unchanged," Rick says, "Olneyville has always been a place for working class people, and it still is."

The river flows on; it is the blood of the community. Before white settlers came, Native Americans farmed the land and fished in the river. In mill times, the river powered industry through waterwheels and dams. Now, at Riverside Park, a rehabilitated industrial site, families and neighbors congregate by the river and the nearby falls.