Casey Shearer Memorial Award for Excellence in Creative Nonfiction, Second Place

"In this game, I show you a picture, and you tell me what's missing," she said.

The first image was a sharpened pencil with no graphite. The wooden cone was cut off horizontally, just where the point should have been.

"The point," I said.

"Right. If you don't know the word for what's missing but you know what it is, you can describe it. Like if you didn't know the word for point, you could have said, 'the little black thing at the end.'" She sounded stupid when she said it that way. And the point would have been more silver than black.

Next a seedless orange appeared, cut in half sideways, missing one of its section dividers. Then a trellis covered with climbing ivy, in a regular lattice pattern except for one area missing a wooden slat. A lace-up shoe with ten holes but only nine grommets.

Then came other images whose missing parts I couldn't identify. I stared at a picture of a touch-tone telephone for many minutes, checking for numbers, checking for letters, and to my disappointment, finding it all there.

I never solved the telephone puzzle. I wonder about it often, but the image has long since erased itself. I'm permanently missing what it was missing.

○

"You only need three," my mother said.

"But there's more space."

○

If you suck one of those red and white-striped peppermints that come wrapped in cellophane until the red dye is gone and take it out of your mouth, the white disk you have in your hand is covered in holes. Those do it. Honeycomb does it. So do the circular cavities left in a pot full of quinoa when it has finished cooking. Plowed snow that has been salted, so that irregular dents melt into it like pores. Coral, sliced pomegranates, pumice, holes in skin. Lotus seedpods are unbearable.

∞

In Buenos Aires I met a poet named Gabriela Yocco who was obsessed with lo no dicho. The unsaid. I started translating her book.

I build my sonorous coffin. With the worn-out hem

of the word I stitch together its magnificent structure.

Later I'll sing la doble lejanía, the furious metal that

composes death, the mysterious wasteland of sleep.

Blood when it gushes.

Later, with my bruised cardboard throat, I will sing.

I couldn't find a translation for la doble lejanía. Lejanía means farawayness. It's the place that seems unreachable and also the expanse between that place and you. It's the place you miss, the place you long for, the place that is so far away and so impossible that it breaks you. And la doble lejanía is that, doubled. Something infinite augmented. It's like multiplying zero by zero by zero and instead of ending up with the same zero, ending up with fields and fields of dry wheat and a throat like bruised cardboard from trying to shout when no one can hear.

The words in English I know for that are four: longing, pining, yearning, and missing. They're unsatisfying. I am envious of the Spanish word for "to miss," extrañar. Extrañar, Gabriela told me once, means taking your innards, your entrañas, and exporting them outside yourself. I imagine meaty sausages, intestines, guts. An abdomen sliced, the entrañas ripped out and uncoiling as they leave the body. The construction of the word implies that when you "miss," when you extrañás, you have internalized something to the point that leaving it behind is leaving a part of yourself there with it, a sensation like the phantom pain of an amputated limb.

Now that I have learned of this other word, I will always be aware that my own language is missing it. I will yearn for it, because it will never really be my own. I will never tell someone, "te extraño," with the "t" properly dentalized and the "r" properly rolled. I will have to borrow the word, or I will have to fill the hole in my own language with missing.

○

In a café at the corner of Lavalle and Riobamba, they sat opposite each other. She wore a cobalt blue sweater with three blue buttons, he a black one that matched his whiskers, which today had grown slightly longer than usual.

"Cuánto falta para que te vayas?" he asked. How much longer are you here? (But really, how much is lacking before you go?)

"Two months," she said. "A little more than two months."

He held his fork hovering a few centimeters over his risotto as if he had forgotten about the food below, and looked at her. A vein was popping out on his forehead.

"Qué," she said.

His fork lowered back into the risotto and he shook his head. "Nada."

Qué?

Nada.

○

I am trying to figure out what missing means, I used to say.

"You mean like nostalgia? Or like the lack of something that's supposed to be there?" people would say.

"Yes," I would say. "Like everything."

Daniel, a boy in my house with Asperger's syndrome, said, "Missing is the psychological pain that one believes would be alleviated if one were near the certain person, place, or thing in question."

I don't really know Daniel.

○

Miss out

Miss a beat

Miss the boat

Miss the mark

Missing Records

Missed it by a mile

Missing Links Found

He does not miss a trick

A miss is as good as a mile

Billions in Oil Missing in Iraq

That iPhone Is Missing a Keyboard

Hundreds Feared Missing From Typhoons

Millions of Missing Birds, Vanishing in Plain Sight

○

Shell Silverstein's children's book The Missing Piece begins with a drawing of a white circle with a wedge cut out of its side. "It was missing a piece," the first page says, "and it was not happy. So it set off in search of its missing piece." It encounters squares, circles, and triangles that don't fit. It tries wedges that are too big, and wedges that are too small. It searches for the part that will complete it, but it doesn't know what that part will look like or feel like. It doesn't know what it means to be whole.

○

"To miss someone simply means that wherever you are, they reappear in your thoughts," Jon told me once.

What does it mean for someone to reappear in your thoughts?

Could the reappearance of someone not there ever be simple?

Is it like teleportation?

∞

Cómo pudo erguirse así, tan hierba?

How could she sit up straight like that, tan hierba? Tan hierba? So grass?

I said to Gabriela, "I can't translate it 'so grass' in English. It sounds ridiculous. What is the most important property of the grass? That it's green? Fresh? Straight?"

"That it's alive," she said.

○

I read once that every country in the world has a word for homesickness, and that scholars from each country claim that their words are unique and untranslatable. "They say that benkshaft is like that," Anna said. Benkshaft is Yiddish. As a noun, it means nostalgia. It's also a verb, and a state of being. "But every time I hear it used, I substitute 'longing,' and it makes perfect sense," she said.

Perhaps it's unproductive to wonder whether there are true translations for things. For some words, there obviously aren't: taarradhin, the Arabic noun meaning, "I win, you win," for example. But maybe the difference between benkshaft and longing is no greater than the difference between benkshaft for one person and benkshaft for another. After a certain point, there is no way to test whether our meanings collide.

○

I called my father, a general surgeon, to find out if he had anything to tell me about phantom limbs.

"Yes, that's a real phenomenon," he said.

"I know it's a real phenomenon, Dad. I've been researching it all day."

"I would Google 'phantom pain,'" he said.

"I was just wondering if you had anything to say about it. Phantom limbs, phantom pain, amputation-what about amputation? Do you have any stories about amputation?"

"I've seen many amputations."

"So, okay, what does it feel like to do one?"

"I can tell you what it's like from the surgeon's point of view. But I would have to think about how that connects."

Don't worry about the connections. Just tell me anything. Sensory details. What does it look like when you cut someone's limb off? What does it smell like? Why might you do it? Do you have some anecdote you remember about having to amputate someone's limb?

Silence.

We weren't colliding.

But then, when we did it was by accident.

"Honestly, Sara, I never really liked amputation," he said. "I'd rather take out an intestine and leave the person whole."

○

First, people only lost their limbs by accident. Then sometimes as punishment. It wasn't until the fifteenth century that surgeons began removing them on purpose-the ones that were severely damaged or infected. Now they are usually cut off because of peripheral vascular disease, where blood is not circulating to the limb, as if it has been forgotten. A limb is amputated when its absence will save the rest of the body.

There are lizards who shed their tales when predators attack, and grow them back. Some worms and sponges can be cut into many parts, and all of them survive. But humans just go on missing their pieces.

Some amputees continue to feel their missing limbs moving, hurting, itching, heating up and cooling down, even when there's nothing there.

I recall Daniel's definition of missing. Missing might be false. It's the belief that the pain would be alleviated if one were near the noun in question. But people believe in all sorts of things. Voo-doo. God.

What if all this is fake?

What if in the end it turns out that I am not merely talking about nothing; but rather I am not talking about anything?

∞

The more you think about a memory, the less accurately you remember it. You wear down the pathways that the actual situation created in your brain, and instead mix them with other possibilities until you can't distinguish what really happened from what could have happened. Actually, the best way to keep a memory intact is to never think about it again.

Maybe all things are destined to go missing in one way or another. If I witness something but never revisit it in my mind, it might as well never have happened. It drops off the record of my consciousness. If I witness something and later I long for it, not only do I miss it in the sense that it reappears in my thoughts, but also in that its details chip away from it like a cliff is chipped away by the ocean. Invisibly, gradually, its chips not really chips but nothingness.

○

Ruth poured her rigatoni in the boiling water and left the pot covered while she turned away for a moment. When she came back and lifted the lid, all of the rigatoni pieces had lined up perpendicular to the bottom of the pan. A tessellation of holes jutted out at her.

I recall the lotus seed pod. The inside of the pomegranate, the half-sucked peppermint.

I have a fear of clusters of holes. I am not afraid of them like I am afraid of violence, or embarrassment, or death. I am disgusted by them. They make my throat drop into my stomach, my insides somersault.

I suppose you could say that it started with this. Before the obsession with the unsaid, before the impossible translations, before missing anyone in particular, before the word missing itself, there was just this. Holes.

Some people are agitated by holes more than others. A woman with trypophobia wrote on her blog that in her painting class, students were instructed to paint their fears. She painted a woman's abdomen with holes in it and maggots coming out of them. She said that it made her feel so sick that she couldn't finish the painting.

It isn't always just holes that give me this feeling. Sometimes it is the realization of the vastness of even a finite volume, and the thought of how many billions of smaller entities could get packed into it. The clusters of tininess, and of the grooves and crevices and extra space trapped between them. This is not like a fear of heights. It has nothing to do with what could happen, what is in the space or what could come out of it and whether that would be dangerous. This fear is just an image.

○

I am planning to send you a message in a bottle, but with no message inside. Perhaps the bottle will be empty, or perhaps I will put a piece of blank paper in it. Or a piece of paper transparent like cellophane. Or reflective paper like a mirror. I wonder what you will think. I wonder what message you will read in it, even though there will be no writing to be read. I wonder what you would think if I sent you a palimpsest. A paper of my lists, erased, and written over. You say that every inside message must have an outside message. I asked you if you can have a message with no packaging, but I did not ask you about packaging with no message.

○

I received your reply to my transparent message. (In the end I decided on acetate, because it was visually closest to nothingness in a bottle without being nothingness in a bottle; I also congratulated myself on the pun on transparent, for my meaning wasn't.) You sent me back an envelope with no return address, though to me your handwriting is as good as one: I would recognize anywhere the tail of your "t" trained through years of using it as a variable for "time." Between two pieces of brown cardboard, I found an unlabeled silver CD-R in a white sleeve. It had a silent audio track on it.

There are so many things one could hear in thirty seconds of silence, if one were really listening. Not so much listening with the ears as with the eyes. It feels more like reading.

The universe is expanding.

I sent you back a Word Document with text in it, but the text was white, so it looked like this

but really it said some other things, about the laws of thermodynamics and about me and you and childhood and extinction.

The word "reductive" keeps coming up

(at some point, something must have come from nothing)

I. Renewing library books should be impossible.

II. The more you think about a memory, the less accurately you remember it.

III. You can never reach absolute zero.

"So, for example, one has less knowledge about the separate fragments of a broken cup than about an intact one, because when the fragments are separated, one does not know exactly whether they will fit together again, or whether perhaps there is a missing shard."

I don't know when this will end, because the silence has become so substantive. I sometimes think I used to know what it meant, before it grew so many arms and legs and tongues. I think it probably boiled down to about three words. But now it is like a third person here, and even when I create it I don't always know what it says. I could not translate it if I tried.

○

Graphite is formed in very thin layers of covalent bonds between its carbon atoms. Stacks of sheets one-atom thick. The layers never actually touch. They hover on top of one another.

This is the reason that graphite is erasable. Its tiny fragments stick to the eraser more readily than they stick to each other. Maybe most things are only erasable if they are narrowly missing each other. If you can erase someone from your memory, never miss her again, maybe you weren't really touching in the first place, but repelling each other at infinitely small distances.

But of course we all know that nothing is ever really erased.

○

My mother said my use of "collision" was troubling.

"You say 'not colliding.' Isn't this just a failure to communicate?" she said.

There's a scene in Annie Hall where two cars are driving toward each other in the rain at night. Alvy Singer, shaking in the passenger seat, watches the road from behind the windshield wipers and waits for the driver of his car to swerve into the oncoming traffic so that the cars smash, head-on. This is what my mother thinks of when I say "collision."

When Dwayne, the driver in the movie, doesn't swerve and the two pairs of headlights pass each other centimeters apart in the rain, we're relieved about the "near miss." This is why, yes, I mean collision. If the cars were several lanes apart, we would never call their not hitting each other a "near miss," or even a "miss." What makes the situation special is that they come so dangerously close on the highway. The closer two cars come to a collision, the more of a "miss" it is.

A collision has to be exact. It has to be generated by motion at high speeds; it has to be violent. It has to be if and only if, this word and nothing else.

They say that at the beginning of everything, before space and time, there was only light, and god poured it all into a vessel. The light was coming in from all angles, straight, angular beams, packed, dense, very dense. The moment god put the cap on it made a little click shut and then the vessel exploded, the shards and light flying everywhere, in billions and billions of pieces.

Every time I add a fragment, the missing conquers a wider expanse. I have a gnawing sensation that I cannot articulate what it is I am trying to say. It is building a universe of restlessness, a world in which missing is the main thing that exists. Perhaps I need to determine what the limits are. What constitutes missing, and what simply doesn't.

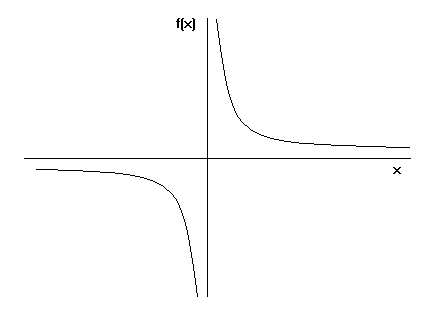

In math, you can find the limit of a function even if the function does not exist at a certain point by approaching the limit from the opposite side. You can do this to determine the limit at a removable discontinuity, the small blip in a smooth function that simply has a hole at the point you are trying to test. You can also test the limit from both sides in functions with asymptotic discontinuities, but only to determine that the limits don't exist.

I am searching for the place where it all coalesces. I must look at it from the opposite side. Find what doesn't have enough space, what isn't missed, what shrinks the expanding universe into a word I can chew and spit into the palm of my hand.

But I worry that what I have on my hands here is not merely a hole but an asymptote, like in the function y = 1/x

where the closer I come to approaching zero along the x-axis-something finite, central, something manageable-the farther away I get on the y-axis. I can approach it from any direction but range of output values explodes.

∞

Sara,

While I might not recognize you now, I do remember you. Your recollection of the test is amazing. There have been changes to the WISC. The Picture Completion Subtest is now optional, and I rarely give it. You were correct about every item including the grommets. The telephone image has been removed, so I can tell you that it was missing the curled wire connecting the phone arm to the base.

Sincerely,

Santa Cucinotta

(Sometimes, just sometimes, there is an answer.)

○

I decided to translate tan hierba just like that, "so alive." Its meaning began to pop up in other places. Things that were "tan hierba" were things that deserved to be embraced because they were living, even if they were painful. The way butter tasted different in the United States and in Argentina. The way there was no translation for la doble lejanía.

○

"There's only one answer," I said to Gabriela. "It is, and it isn't."

She looked at me. "That's two answers."

○

Language doesn't reach everything. The absence of language doesn't reach everything. Language plus the absence of language doesn't reach everything.

○

Last night we were all floating on umbrellas in the sea. The water was filled with them, white and turned upside down like teacups. We were drifting with the current, and we didn't know where we were going.

Suddenly, the wind under my umbrella turned fierce. Someone shouted, "You're moving, Sara!"

I moved fast, as if I were surfing, deeper into the sea, farther from the shore.

I still didn't know where I was going

and at the end of the dream, the word pronounced was alcance.