|

The Assyrian men drank heavily in the hall, passing horn after horn to one another. They drank until they could drink no more, each heavy horn brimming with the equivalent of a six-pack. The hall smelled of old beer as it mixed with grainy dirt and struggled to dry on the floor. But according to tradition, these men were behaving well-drinking too much was following the rules. The oldest man had to ask for special permission to drink less than the younger men. Holofernes, leader of the drunks-who would now be one of those boys forever clad in a half-unbuttoned dress shirt with slick, reflective hair-was in the hall that night. He may or may not have passed out in his tent (picture the decorations: all dirt and blood and failure) after he may or may now have tried to unromantically sleep with Judith. She, a Bethulian, was the one getting the most out of the inebriation; her sober pride was greater than any amount of drunk treachery and confidence. Judith would not sleep with the brute. She was a powerful woman, a hero even, and she had her dignity to maintain. But she and the Bethulians also had a war to win, a determination to drive the Assyrians into dust, create a new desert or dust bowl. So she resisted the pull of potential satisfaction (though we must now doubt Holofernes' sexual skill in his stupor; a slow sloppy dance in his tent would have certainly been a mistake come morning). Judith was the one with the sword. She chopped off his head in one blow or two-a slice halfway through, perhaps, though the broken Old English poem will never give us what we want. The sound was smooth, no crunching of spine and sinew, no spattering arteries. A simple movement, a delicate murder. Is this a persistent fantasy? Meanwhile, the other characters, nameless with faces swept away in copies of copies of manuscripts, never seemed to notice anything strange about such a strong female hero in a battlefield of men. Judith's handmaiden, always a loyal servant, carried the head in a bag as Judith led the Bethulian troops into battle against the Assyrians. But the Assyrians were in mourning after the shameful murder of their leader. The Old English poet did this, not God. And it was up to this poet, in the end, to have Judith lead her troops to victory against the Assyrians, who fell conquered by the woman with the sword, the woman who would never be lost in scribal error or torn vellum. Judith suffered little. |

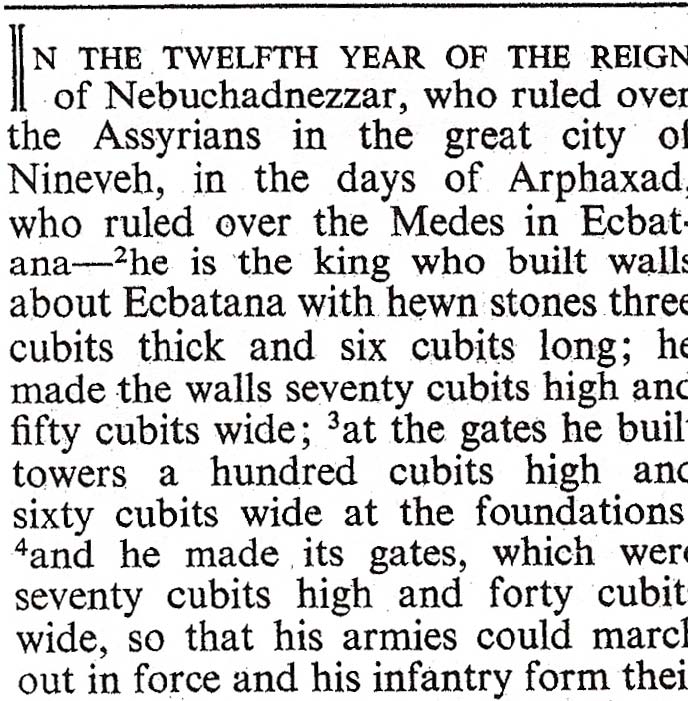

In the Bible Judith is frail and ready to snap in battle. But she was there to trick Holofernes and his fellow Assyrians. She came from the Israelites promising to tell Holofernes their secrets and perform the most delicate sexual favors. What would be the order? Sweet whispered nothings about the Israelites' plan of attack as foreplay? Or after, the two in bed, smoking anachronistic cigarettes, exhaling the secrets into the stale air of Holofernes' tent. The feminine mystique was there-she was a regular woman using a regular woman's tricks. But notice: in the Bible she is a widow-needy and empty without a husband to fill the void presented by simply being a woman (for there is no greater shame than the weaker sex making itself strong, at least if these words are to be trusted (and they came from God, didn't they, the undying unquestionable truth)). Judith chopped off Holofernes' head and gave it to the Israelites. It was a prize worth preserving, the impetus to complete what was bound to be an excruciating battle and retreat. But the battle is small and fits between the tiny lines of Hebrew (then Greek, then Latin, and now the unspeakable in consonants bound for vulgarities). It was swept away in God's hushed musings, swept away by Judith's beauty. The Assyrians were pushed off the map by Judith's sweet breath (but hadn't she been drinking that same beer, that same stinking beer). The troops scattered and Judith remained a widow and the Israelites saw success. Judith suffered. |

|

|

|

| Beginnings, already riddled with wonder. | |

|---|---|

It is up to the scribes to make the poem exist for longer than the night.

The Old English poems are made of half-lines, which now, with proper formatting, become two sturdy columns down the page. Each A verse half-line resolves in the B-in sound and meaning, hard work and the pleasure of listening. The minor pentatonic slides into the major so no one notices until they feel the heat under their cheeks, a creeping happiness replacing a cool blue. And there was alliteration too-so much for the scribe to keep track of, these smooth sounds and intricate stories, rhythms binding and syncopated.

But before the poem was the Bible, a story with a less powerful Judith and a less powerful poetry. Judith moved from the Bible to the poem in a deliberate shift: the creation of a new hero, demolition of a beautifully passive floozy.

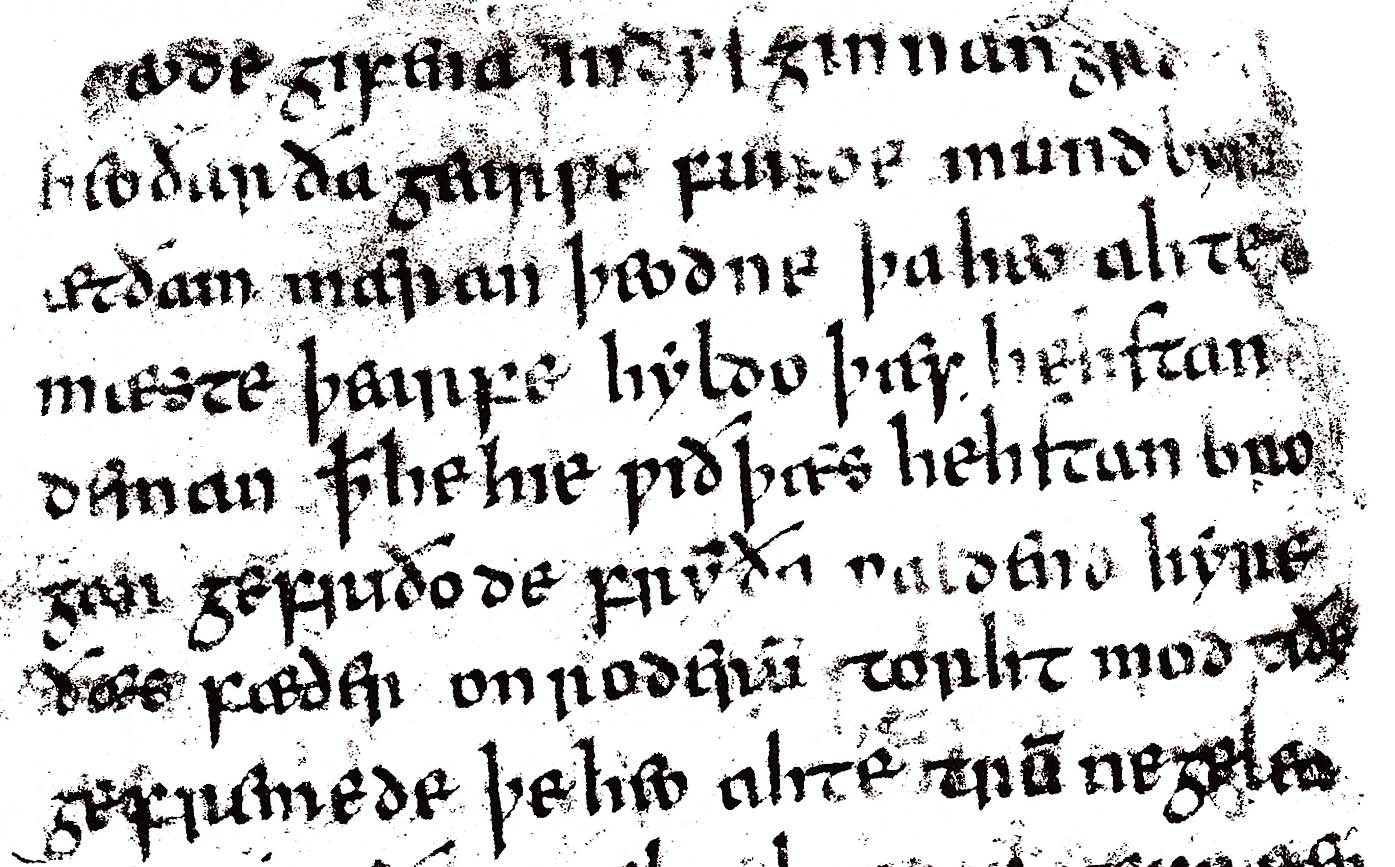

She journeyed through many manuscripts and the scribes made mistakes. They didn't know her story, the importance of putting space between the Old English poetry and the dirty Biblical prose. They didn't know the violence in the A half-lines and forgot the resolution in the B, a lack of columns facing off for inevitable joining. Some scribes just wrote straight across the page, denied the poem its poemness, turned the lines to prose and broke the line-breaks. They mashed words together to make them fit in the tight margins of luxurious vellum. Would you like the job of writing without thinking? Would you learn the language or just copy mindlessly, turn the story into visual beauty but leave its meaning behind. The page is deflective.

There are too many translations, too many mistakes. We find pleasure in each translation, comfort in the errors until they start to distract. Each version feels right and then devolves into meaningless lettering and cramped words. But here she is, typed and copied, a hero at last, finally.

Also hidden: Judith barely fits into the margins of the Beowulf manuscript. She exists in little scribbles next to beautiful lettering and illuminated capitals, a woman hero overtaken. And she may be incomplete; the beginning may not actually be the beginning-a false start to such a blasphemously true tale. The middle becomes the beginning, becomes what is remembered. Loss is fortunate.

How much of the poem is formula, improvisation, rhythm? We get lost in the sounds of the language and forget the violence within. Does this still happen in thick novels and shrinking newspapers? We can start to live in alliterative half-lines and emerge, after so much time, numb to the stuff of language. We only hear sharp sounds and the slickness of letters that start words.

Judith's beauty is in the sound of that dead language. It is not in her golden locks or delicate walk, the way she can waltz away from a bloody beheading still a lady, still unblemished. It is the galloping rhythm delivered in improvisation and without the page to suck in meaning and throw it to the reader as a regurgitated mess of symbols and mistakes.

The Old English poet must write his poetry on the spot, writing by reciting, a process fueled by language and beer. The lines' rhythm captivates the crowd, turns the poet into the deejay of a hall party, the center of attention and momentary hero.

The loss of the author. Maybe a woman.

NOTICE

Judith is called "ides ellenrof"-"courageous noble lady." She takes over the rough language effortlessly, the rhythm of each half-line unbroken, a gentle step in such a choreographed path.

Judith's hair is beautiful. It is effortlessly smooth even after battle. She is the type of woman who refuses to put her hair up. She has the allure of any woman who holds a sword.

There is something missing in the manuscript.

Do not be threatened by Judith.

Call her benevolent hero.

| CONSIDER | CONSIDER |

|

Today, would the poet use the word fuck? And if he did, would he italicize it, make its points duller in a slight lean forward? |

Was the sword really sharp enough to cut through such a dense neck, toughened by days on horseback and nights holding up the heavy head of insobriety? Do nerve impulses travel fast enough to feel the first pierce of the sword before it works its way to the other side? In other words, did Holofernes suffer? Let him notice everything but his demise. Let him notice the great night he could have had only to wake bleary-eyed in the morning. "If the instrument was blunt or the executioner clumsy, multiple strokes might be required to sever the head." |

SO THE POEM BEGINS, BASTARDIZED IN ENGLISH, SLAIN BY MODERNITY, AND OTHER MELODRAMATIC DESCRIPTIONS NOT QUITE FITTING FOR SUCH A LOVELY POEM ABOUT SUCH A LOVELY MURDER:

|

Reward is doubted of a fair share in this wide world. the helping hand of the great Guardian grace of the highest Lord, creation's wielder, against highest threat. |

Yet therein she found abundantly when she had most need, for by him she was shielded, |

| (But before: | |

| doubted of gifts in this great creation. protection at the hands of the famous prince then the grace of the highest Judge defended lord of beginnings. |

She there found readily in God that she most needed that he her with great protection brought |

| (And much before: | |

|

tweode gifena in ðys ginnan grunde. mundbyrd æt ðam mæran þeodne, hyldo þæs hehstan deman, gefriðode, frymða Waldend. )) |

Heo ðær gearwe funde þa heo ahte mæste þearfe, þæt he hie wið þæt hehstan brogan |

The copies were garbled piles of letters, runes written atop one another. There is so much lost. There is too much lost. There is uncertainly in the loss. There is fear in what could be lost. So much is lost.

These copies had no sound (now none, destroyed at last), no rhythm. The language loses its music, the tap tap of hard consonants and crescendo of long vowels. There is no care for the language; it is extinguished in careless lettering and shaky hands. Maybe there was not enough light.

So lost that maybe it didn't exist. Maybe it is only comfort. Maybe there is no satisfying beginning to the beautiful poem. When does the original poem stop existing? Is it when there are more versions unlike it than like it? Or is it when the rhythm feels wrong because it is so rhythmic, because we are used to the mistakes and have started taking them for truth. Beauty is lost, or beauty is replaced.

Judith is starting to disappear. She outlasted the language, its slow and deliberate death, outlasted the Biblical chauvinism and mystery, outlasted such brutalized copies. But she is fading, slowly, surely, towards aching end.

TURNING AWAY BUT GLANCING AT THE REFLECTION IN THE DARKENED WINDOWS, FINGERPRINTS FOR EYES OR BLUSHING CHEEKS

Gregory Rabassa translated a lot of Gabriel García Márquez, and his ego increased with each translation. He wrote a book about how he's a really good translator. Even the front of the book says this (but it's actually a reviewer writing it, not Rabassa saying it, and here we find the difference between speech and writing, between reciting Judith to a crowd of drunks and copying it nervously in candlelight and dust).

| Gregory Rabassa writes: "There is more to it than this. If a word is a metaphor for a thing, why does a single thing have so many metaphors in orbit about it? Here we have the dire consequences of Babel." | Gregory Rabassa writes: "It follows, therefore, that life is an idea, a word, in short, a metaphor for conscious existence and hence a translation. We are translating our existence and our circumstance as we go along living and before we are fatally assigned the translator's lot once the treason has been done: Segismundo's tower or tomb" |

But his manuscripts were typed, little space for letters combining, turning to new words, new sounds. Then destroyed by mistake and carelessness, rushing through the chore of language. Destroy the chore, destroy the language-Judith is breaking, maybe never was.

There is always the threat of losing the rhythm, Spanish to English, Old English to English. And maybe these words are to blame, these harsh sounds jammed together in letters that clack and tick, not letters that blush and wave, drizzling into each other like a slow rain. We concentrate too much on the consonants, the toughest sounds. There is little room left for gentle beauty. Then: there's a glimpse of it in Judith, in the very act of translating, of moving her story forward. But we retreat when the stories differ, when the source itself is as unclear as the proper word order in modern English, when the letters lose their shape and crispness, when the symmetry of lines is lost in crushed and torn margins.

And inside those lines we find more loss. The inability to translate accurately. The admittance that something must be lost, that it can't be avoided. There are no single words that mean, for instance, "drunk from drinking too much wine" ("windruncen"), only different words for drunk. Does this reflect of the love drinking different kinds of booze jumbled together? Or is it that we don't demand enough precision from our language and then don't notice the lack of precision until we start to make comparisons. Or until we start to drink.

The modern poet, at a loss with this loss, might tell Judith's story in broken verse, free verse, or a verse so bound by mathematical constraint that the words are no longer words (a slight return to the centuries of manuscripts copied by mistaken scribes). Judith's poet was bound by rhythm and sound and story

and women.

So Judith is trapped and not trapped at once. She is lost in a dead language, but she is escaping from the edges of mistakes and photocopies, translations and retellings. She is struggling to exist without the means-the words-to stay afloat. The text walled and contained the action until it became so different that it could hold no one and nothing, not even the faces of would-be characters. The scenery was erased, nearly, only fierce animals and foreboding skies. But the mistakes were so obvious and Judith climbed higher and higher towards surface, a presence in struggling language.

What to do but to help with the struggle. To prevent complete loss or even the fluky short-term memory of once-memorized poetry. To save the hero, the new hero, the hero already saved from the depths of the Bible, from the depths of variant translations, from the depths of modern typewriters and overhead projections. To lure Judith into living again.

NOTES

Beheading quotation comes from: www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/decapitation

Rabassa quotations come from: Rabassa, Gregory. If this be treason: translation and its dyscontents. New York: New Directions, 2005