Honorable Mention, The Casey Shearer Memorial Award For Excellence In Creative Nonfiction

This is how I leaned the syllables of your name.

Ma. Liu. Ming.

First in pictures. And then the meanings.

"Six Bright Horses," Mateu translates, when I ask him. He speaks some Chinese after a tempestuous love affair with a drag queen from Beijing. (I would never have believed this if I hadn't been privy to the bilingual and violent break-up: Brooklyn Bridge, August 2005.) "That's what it means," Mateu says. "I mean, your intonation is all wrong, but I think that's what you're getting at. It's a name, right? Where'd you get it from?"

*

Almost three months later, we will break into the basement of the biomedical center right before midnight: Mateu and I. We'll balance on our toes and move like raptors through the subterranean halls. We'll both be wearing heels. His are stiletto, mine are platform, and sometimes we'll reach out to steady ourselves against the metal lockers in which (I've always imagined) the med students keep spare kidneys, punctured lungs, toes they've amputated by accident.

The swipe-card that gets us into the building belongs to Jason, a second-year med student we've co-opted along the way. The combination code that gets us into the morgue is his as well. "It isn't pretty," he'll say, right outside the locked set of double-doors. "It isn't like a funeral home or like what's on TV, okay, it isn't…nice."

Mateu will cut in, impatient, bouncing on his toes, the metal bangles around his wrist clinking even as he'll try to keep his heels from clicking.

"It's fine," he'll say. "I want to show her Giovanni."

"Giovanni?" I'll ask.

"Yeah," Mateu will tell me, "He's the best, he just came in the other day and he's got cheekbones to die for,"-and while he's still laughing and Jason is still mid-sentence ("Mateu, show some respect all right-") Mateu will punch in the six-digit combination and pull the doors open. "Let's go, rockstars," he'll say, sashaying ahead of us into the unexpected warmth of the morgue. But that will be almost three months later.

*

I ask Mateu about you because of anyone, he would know. Mateu knows everything, always, and sometimes I hate him for it. Mateu once tried to teach me Chinese, but I foundered on a word I can't now remember that, depending on the intonation, might have meant either six, snake, wet, or death. So now when I ask him if he's ever heard of the East Village, his first thought is New York and he laughs and then informs me that when he was fifteen and sixteen he performed drag all over the village.

"No," I say, "I mean the other East Village-China, right? Wasn't there an East Village in Beijing?"

"Beijing," Mateu echoes, "What do I know about Beijing?" We are sitting outside the med school on a low cement wall, waiting for Jason, and Mateu is smoking his trademark Gauloise and ignoring the glares of passing med-students. He rethinks that sentence right after he says it, and grins around the Gauloise. "Okay," he amends, "but that doesn't count because we never left the hotel room, like forty-eight hours and we were there the whole time just drinking and fucking."

I sigh. "It's a suburb of Beijing," I explain, "I know that much, there used to be a colony of artists there, I think. But didn't something happen to them in the mid-90s? Didn't the government close them down or something?"

Mateu narrows his eyes at me and then turns his head to blow a stream of smoke in the direction of a med student who is just exiting the building.

"Since when did you care about Chinese history?" Mateu asks.

"Never mind," I tell him, flipping my collar up against the cold.

"Hey!" the med student calls after he is safely across the street, "Cancer kills, you know!"

*

When I first saw your picture I was coming off a Chicago street, smoky and bright with December cold. I was sheltering against the wind in the arch of the Smart Art Museum and I couldn't decide if I wanted to go in or not; then all of a sudden a sharp wind cut through the street and sliced at my eyes, and I swore, shouldered the door open, and slipped into the startling heat of the museum lobby.

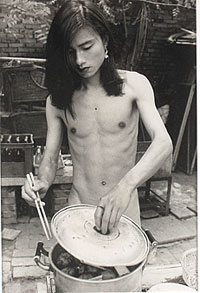

From the moment I came upon you-naked, the long strokes of your body balanced on the stones of the Great Wall-from that moment, you were like human calligraphy. I walked across the echoing tiles of the museum lobby, through Avant-Garde Art and Ancient Egypt and past the Japanese scrolls. I walked into China and stopped right in front of you, stared at you, and you stared back calmly.

You were so calm.

So I followed you, that afternoon. Through frame after frame, from room to room. From the Great Wall to the East Village. You were in a bathroom, posed in front of a mirror, bare hip jutting, smooth shoulder-blade, applying lipstick to your swollen lips. You were in a bath-tub, head lolled back against the white porcelain wall, eyes half-closed and black tufts of cut hair furring the water like blood. You were painting in the clear half-light of a studio. You were balanced on the edge of a torn armchair in the middle of the street. Always balanced, always precarious, always composed. Always naked: the muscled arms and flat hard torso of a man and the high curved face, the long slender hands, the hips of a woman. Fen Ma-Liuming, the captions said. Performing as Fen Ma-Liuming. And "Fen" means other, it means different, I looked that up on the internet and some sites said that Fen implies female. And that made me laugh because when you pursed your painted lips and swung your hips-well. That's a little more than an implication.

*

There's a story about Mateu and the Dean of the Medical School, and the story goes that back in October he went to her office to talk to her about his acceptance to med school for the next fall. And I can just imagine it-the cool sterile white of the med school and then Mateu like a breath off the equator-cinnamon skin, black leather, high-heeled boots, the metal at his wrists and throat, the rings in his ears, his accent: Trinidad making love to Rio and every word is pure silver. The interview went well but at the end of it the Dean leaned forward across the desk.

"Medical school is a serious commitment," she said, "And I just want to take a moment to address your-choice of-apparel, I suppose. You'll be taken more seriously if you dress like a man. After all, that's what you are, isn't it? Aren't you a man?" -And Mateu without losing a beat, without shifting in his seat, without losing a sweet bright chin-lifted moment-Mateu crossed his legs, narrowed his eyes, and said, "A man? Senhora, you can call me Mateu when I'm wearin pants, but when I'm in a mini-skirt, you best be callin me María."

*

And here's the thing: I wasn't one of those thin American girls with an eating disorder. I was never one of those American girls who won't be happy until their bodies are nothing more than a storage crate for their organs, whose every rib is a splintery slat, who have do not open stamped across their mouths. I never restricted myself to a diet of lettuce and water, I never snapped rubber-bands around my wrists to remind myself to look away from the peanut-butter. I have never hated my body with that intensity.

But I remember the moment when I knew that it was simply incorrect. I was nine years old and I was the wrong answer to the equation I'd been solving. I couldn't erase it and start over, too late for that. And so I stopped looking in mirrors, I wore blue jeans and over-size button-down shirts. When I was thirteen I woke up breathless from a dream in which I was a man.

It's possible that the first thing I noticed-about Mateu, and then about Ma Liuming-was the fearless clarity in the way they stood. Every muscle and sinew speaking to itself, to the bones, to the veins in their wrists, to the arches of their feet. Because they were becoming what they needed to be, everything a smooth deliberate conversation of parts, an evolution toward something like hope.

*

There are facts, too, although those come later, gleaned from obscure articles in art publications, from the web-pages of international galleries, from the curt responses of gallery owners whom I email with growing desperation. Ma Liuming isn't alone. There is Zhang Huan, fists clenched in every photograph, head thrust forward, built for a fight. And there is the photographer Lii Zhirong (more commonly known as Rong Rong) who started out as a passport photographer in Beijing and ended up in the East Village ghetto documenting a reckless, transgressive genderbending performance art that will bring the police down on their heads with charges of pornography by August of 1994. There are facts, and I gather them close, store them like delicate plants-never too much direct sunlight. Having left the museum back in Chicago, eight hundred and thirty-eight miles away from Providence, Rhode Island, I print grainy reproductions off the internet and tape them to my walls.

*

August 1994. I would have been nine years old, then. I would have still believed in the complacent binary of man bodies and women bodies. I couldn't have imagined the meeting-place between the two-the broad well-muscled back of a man and the sculpted hips of a woman. I would not have known of the term "gender dysphoria." But I do remember that when I was nine, my parents told me I couldn't play basketball with my shirt off anymore. And I remember how deeply I felt cheated. Betrayed by something inside me that was swelling, expanding, devouring me and making me-against my will-into a woman.

*

Why are we this hungry? Why are we so hungry?

I don't ask Mateu this. But I watch him-he is giving me a lift home, fifty miles per hour on streets marked clearly twenty-I watch his long carefully manicured fingers on the driving wheel, his heeled boot on the gas pedal, the glint of metal in his ears. In my pocket is a piece of paper folded in fourths, it came in the mail today from an art-gallery owner in London.

In September of 1999, Mr. London writes, I had the pleasure of displaying several of Mr. Zhirong's black and white prints of a number of East Village artists, among them the man you inquired about, Ma Liuming. I have not had personal contact with Mr. Ma, but I have heard that he is currently living and working in the Beijing area. Why don't you try and contact him through Beijing galleries?

Sometimes, waiting in the cold, I play with the zipper on my jacket and wonder: is there some hidden seam in my skin, cut in the right place and it all slips off?

Sometimes I wake up from dreams that I barely remember and find my hands clamped over my chest, and I am surprised by the vague dream-memory of flatness there, of something hard between my legs.

Sometimes I look at Mateu's old biology books to remind myself that through the desperate force of your own propulsion forward you can change the shape and contour of your body. Look at amoebas. Look at jellyfish.

Sometimes when I swallow I think I hear it echoing inside me.

Sometimes I think: Mateu and me, we're too young to be this hungry.

*

Mateu goes out in the blizzard-because, he says, it's Friday night and a girl's gotta dance-and I sit outside the library in the snow and watch the ice form layers on the sidewalk. Driving back through the city streets, Mateu sees me at the side of the road. He skids to a stop and blasts the horn.

"The club was closed," Mateu tells me as I clamber into his car. His eyes are outlined with kohl, his lips deep red; he is wearing snakeskin boots. He is a beautiful approximation of a woman, built on the inerasable bones of a man. I stare down at my own wrists. They are slender. The bones of a woman. Or a boy. When Mateu is idling the car at the curb outside my apartment, he turns to me and sighs.

"Meu Deus," he says, "What now, hmm?"

And that's when I look up and ask, "Are there really dead bodies in the biomed center?"

*

I only ever read one interview with Ma Liuming that was translated to English, and in it he never even said what it was that he'd wanted, that he'd intended, or if he knew what it meant: the stark, calm enigma of his naked body. He said that when he performed it was as Fen Ma-Liuming, the woman; that he hadn't expected either to be arrested in August or released a few months later; that he was aware that he disturbed people, but-he suggested softly-maybe wasn't that all right? and that it wasn't drag, he wasn't even gay, it wasn't as much performing as it was becoming. But he didn't specify what that meant, either: performing or becoming. In the end of the interview he said that he didn't regret any of it, he wouldn't have done anything differently-and I was glad he'd said that, but I wished there had been more, because he didn't talk about what it's like to strip down to the surface of your skin and walk the length of the Great Wall of China.

*

Giovanni's face is covered in cheesecloth, the whole front of his chest cut open and lifted off. The first thing I notice is the smell: like sweet, deep yellow: something medical that covers but can't conceal death.

"Hey Giovanni," I say, trying not to breathe in.

"Here," Jason says, taking charge. "Hold this," and he offers me Giovanni's opened arm. I take it carefully in both of my hands, and Jason peels back the forearm tissue, exposing tendons, veins, the secret rod of bone. "Look," he says, and, catching a tendon between his glistening purple latex fingertips, he pulls. Giovanni's index finger moves, perceptibly, back and forth. Beckoning.

"Nossa!" Mateu exclaims, "That's amazing. Que legal, né? Let me try," and he gives me the dead weight of Giovanni's hand so that he can find the tendon. I look at Giovanni beckoning me, then free my own right hand and make the same gesture. I look at Giovanni's yellow tendon, trapped between Mateu's thumb and forefinger, and then down at the smooth expanse of my own wrist and forearm. It is when I look back up that I notice Giovanni's fingers, long and slender, skin peeled back from fluted bone, delicately intertwined with my own.

When Jason and Mateu walk into the next room to throw away their gloves, I'm left alone with Giovanni. I stand looking down at him-the high sharp shape of his cheekbones under the cheesecloth, the jut of a Roman nose, the unforgiving lines of his set mouth. In Manhattan you could drop an easy thousand to look like this, Mateu had said with genuine envy, all of us staring down at Giovanni's covered face.

I peel my gloves off: first the clear outer layer, then the purple. I unbutton my lab coat. I lean over Giovanni looking down down down into where he used to keep his heart. It's in the bucket under the table, now. I don't know if I want to laugh or throw up. Flank steak and chicken, that's what we look like inside. Hamburger and roast beef. Something vital and violent and disappointing. This is all we are, I want to say. This is what naked really is. But that's not true either, because what naked also is: the sheets of wet, smooth muscle; the long almond-shapes of Giovanni's fingernails; the perfect open curve of collarbone; the gossamer strands of sinew. If you didn't know what it was, if someone showed it to you out of context, if all you saw were fistfuls of shining strings-man or woman, you would want to clothe yourself in it, it would be so beautiful, doesn't matter who you are, you'd want to wear it close to you.

Mateu, re-entering the room, laughs at me.

"Ay, menina," he sighs. "Meu Deus." He comes to stand over Giovanni with me, both of us glancing down at the gaping crater of his chest. He reaches out, not quite touching, his hand hovering above, and says, mock-serious, "The man was eighty years old, he made a good run of it, but in the end I guess he just lost heart."

*

We're told as children to love what we are. Love ourselves.

But what if ourselves is not what we are?

That's when we take the camera out, maybe. And the snakeskin boots. And the earrings.

But me, what do I take out?

I just want to start putting things back. Wrists. Breasts.

I look at Mateu in stiletto heels, zipping Giovanni back into his canvas dream. I think: I would trade with you. I think: You're more honest now than when you were born.Mateu tucks Giovanni's flayed hand back under the canvas. I look at the fluted bone and think: Either of you.

*

This is how I leaned the syllables of your name:

First in pictures. And then in hunger.

This is how I learned the syllables of hunger, and I've never been full, since.