| Narrators |

|

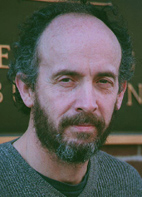

Bob Kerr

Interview and story by: Danielle Savastano |

Growing Pains from Childhood to Vietnam

I was born in 1945 in Cortland, New York and grew up upstate until my high school years when we moved to Detroit. There we lived in a suburb called Grosse Pointe, which was an entirely white, beyond upper middle class community. My parents were both teachers, and I went to a private school called the Grosse Pointe University School. My father taught there, so I was allowed to go there on full scholarship. It was a fairly privileged environment, which was nice in a way, but it was pretty unreal in a way, too. I don't think it got me ready for much of anything; I had a lot to learn once I left there. The social mix was obviously nothing like I was going to be seeing when I got out.

When JFK was assassinated that was the weirdest. Whenever I think, when did things turn? I think that was when they turned. It was just so removed from anything. That didn't happen, it just didn't, but since then it's happened. I think we started to realize that we weren't safe anymore, these things could happen. From then on it was crazy.

I went to Hamilton College, which is in the wilds of upstate New York, which at the time was an all men's school, 800 men up on a hill top, all by themselves. It was a wonderful school, but it was a little monastic. Upstate New York winters are legendary, and eighteen was the drinking age then in New York. That was a huge adjustment, because all of a sudden I could go into a bar where I couldn't in Michigan, so it was a pretty crazy four years. It was a real quiet campus. The biggest demonstration I think we had was when the administration let state police come in and search dorm rooms for drugs, and the place went nuts. That just shows you how spoiled and self-indulgent we were, that that was the biggest thing that would get us upset. I came out of there in 1967 when things were starting to get a little crazy.

I loved rock and roll, The Kinks, The Who, The Stones. I went to an awful lot of concerts. I just loved the feeling. I even went to some of the big festivals. I remember being in Byron, Georgia in a soybean field with like half a million people. Jimi Hendrix was there and Jethro Tull, I loved that stuff.

I remember a lot of people telling me I was crazy when I enlisted in the Marine Corps in my senior year which I did out of lack of anything better to do. I remember I walked into the Student Center at school one day, and things weren't going too well. I'd just broken up with somebody which was a pretty regular thing for me anyway. My grades weren't very good, so I knew graduate school wasn't a possibility. There were two men in uniform there and I thought, why not? That's really flip, but that's about as much thought that went into it.

I ended up taking a test for Navy Air because I thought being a pilot would be great. I was just this incredibly naive. [I thought] it would be nice to fly jets. I didn't pass that test, and the Marines were next. If a person had a pulse they would get into the Marines. The Marines were this crazy leap for me. I'd lived a safe kind of life up until then and I figured I would make the break and go into the Marines and be crazy.

Going into the Marine Corps was a real eye opener for me. All of a sudden I was living in these squad bays in Vietnam with inner city kids. A huge majority of kids over there were underprivileged inner city kids, black kids mostly. I would hear for the first time what they were all about, and I hadn't heard that before. My black experience to that point was taking a cold drink out to the man who would come dig up our garden every spring. My sister was very involved in what you might call racial politics. She worked as a poverty lawyer in Detroit, and tried very hard to give me a social conscience; she sort of sowed the seeds. Without her, I probably would have gone much longer without really being aware of what was going on, she was a great help.

Racially, some conflicts arose. When Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, I was still at Quantico. I was in a squad bay, which was probably forty, fifty people maybe, and this real idiot came through, he was from Arkansas or somewhere, and he said, "Did you hear they're gonna give the guy who killed Martin Luther King the medal of honor?" There weren't that many people in there at the time, but there was a group of Black marines in the corner talking, and I could tell that they heard what he said. He was found in the showers the next morning really beat up badly, and nothing was ever supposedly investigated. I remember some people went to the gunnery sergeant and said, "Look, this is what he said, he deserved what he got." Blacks were just beginning to realize they should have a piece of the action. In Vietnam, they always said the best relationships were in the combat units because they knew they had to get along, but in the rear there were a lot of conflicts. It was just starting to have an edge to it, and I think part of that was because these men were saying, "Hey, we died. We took the shot; we deserve something, and we're not going to go back to the same stuff we came from."

In regard to the draft, I think there were ways to do it that were morally correct. I admired the people who put their whole life, the life they had known, in jeopardy and went to Canada or Sweden or whatever. The people who used the medical dodges or the educational dodges were real hypocrites. Getting some doctor who was a friend of your father's to clear you with flat feet was really the lowest. If you were there, you saw the cliché of the eighteen-year-old inner city kid, and you know he didn't have any of those options. I remember a friend of mine flunked out, enlisted in the Marines and got killed in Vietnam like three months later. That really jolted all of us. It really brought it home in a way it hadn't before.

I was sobbing that day as I left home for boot camp in September of '67. My parents didn't want me to go, they didn't understand why I was doing it. They didn't say, "You're crazy to do this." They were just very supportive. it was a year later when I left for Vietnam. That was a lot more traumatic. The day I left was just real, real tough on them. We held each other in a way we didn't normally do. It was real emotional, and our family was not an emotional family, so it was a pretty heavy moment for us. When I was in Vietnam I lied - the best thing I ever did, I think - I told them I was in a real good area, I was in an air conditioned office, I was never in danger. [Actually] I was going out with Marine infantry units all the time. If they knew what I was doing it just would have been that much harder for them.

Talk about jolting you out of your old lifestyle, you know, I'd gone to Grosse Pointe University School and Hamilton College, that's just about as white and privileged as you can get. All of a sudden I was getting beaten around by these southerners. All the DI's (Drill Instructors) it seemed like were southern guys. It was just ten weeks of being scared and uncertain. I was never commissioned an officer. I was personally disappointed that I didn't make it. I even went up to my DI at the end of it and apologized.

I stayed at Quantico for a year where I was on the base newspaper. They had one opening for my job at Vietnam and I just took it on the spur of the moment. I said, this is crazy to do the Marine Corps and not go to Vietnam. It's stupid. I probably could have hid out in Quantico for the two years, but I'm really glad I didn't.

In '68 when I was at Camp Pendleton, California, where every [Marine] went before they were [sent] to Vietnam, there were a bunch of us watching the Chicago Democratic Convention on a TV set in a store window. They were showing the street madness and we all thought, I hate to admit this now, but we all thought the cops should really bust heads. I don't know why, there was just this sort of mob mentality watching this thing. Afterward, the [police] really rioted, they really lost it. Looking at it in retrospect it was a hideous event, but I remember at the time we were all just standing there in the street, watching this thing on TV. There were guys cheering the cops. I wasn't cheering the cops, but it was weird. It was this very out of time sort of experience that didn't make any sense.

Then I was sent to the northern most part of South Vietnam along the DMZ [demilitarized zone] and Dong Hoi, Quang Tri, and in that area. I was there from September of '68 to September of '69. It was frightening sometimes. We'd get hit. It was frightening to be in combat, but at the same time it was incredibly eye opening. We would go out on missions sometimes and nothing would happen, and we'd realize what a beautiful place it was. I'd sit up on a mountain at night and look out, and it's a stunning country, and I'd think, why is this happening? Other times it would be crazy. The first time I ever went out on an operation the helicopter was coming into the LZ [landing zone] and they yelled, "Hot LZ!" (This is my war story.) I looked out and there were guys lying on ponchos in the landing zone and it was "hot." I wondered why would they be sleeping in the middle of all this that's going on? That was my first thought, I didn't think dead, you know. They were just lying on ponchos just spread out on the ground, and it was very strange. I realized quickly enough that they weren't sleeping.

When I went in 1968 [the war] was starting to turn in terms of questioning. Nothing was questioned for a while, but it was starting to before I went. We would debate the war a lot over there. The purpose of our military presence was to keep the North Vietnamese from overrunning the South Vietnamese. It was a civil war that we were coming in on, on the side of democracy, and it was us against them. It was freedom against communism. It was all the classic confrontations.

When I was at OCS [in 1968], they had the big demonstrations at the Pentagon in Washington, so clarity of purpose was starting to erode even then. By the time we got back, the turmoil was everywhere. We could see the craziness of it. We could see that the real military professionals were allowed to do what they wanted to do. Militarily it made no sense. Politically, we realized the South Vietnamese didn't really have their hearts in this. We were really confronted with a lot of questions and then we'd say, "Man, I hate to die for this, because there's not much point to it." It's so personal. When someone's there, they don't see it in political terms. It's seen in terms of one's friends, and what has to be done each day.

I don't think I really saw it beyond that till I got back.People just started seeing some of the duplicity involved, and what got us in there, and how the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution probably wasn't legitimate. People started to hear a lot of the lying that had gone on and [there was] anger, incredible anger. That was the biggest thing among veterans, just angry that they had been taken. There's a sense that we had been taken for fools. We'd really been had, and people were mad about that. The political awareness came with a sense of personal betrayal more than anything else.

I would say in terms of feeling good about male relationships, [the experience] was great, that's the best it gets. During that time, it was a great feeling. I tended to buy into that whole idea of brothers in arms to some extent. The weird thing is that they always tell you that you never keep those friendships. You always think that you go through this incredibly intense experience with each other and you'll stay in touch for life. I remember a sergeant or somebody telling me that won't happen, and it doesn't. We were saying we were going to have parties, and every year we were gonna get together in a different city, and we didn't.

I was scared, incredibly scared a lot when things happened. We were getting overrun at night once, and I was really scared. It was just a question of if they ran by the hole I was in. The most gruesome stuff was the aftermath...

We were in an area once where they set up these things called fire support bases. What they were was a hill top leveled off, and they would put up an infantry company for security., Then they would set up wire all around. They would put up wires with tin cans and things on them so that if anybody came through at night they would make noise. One night these, what they call sappers, came through. I looked out and there were fireflies; fireflies were very common in Vietnam you would see them all night, so we looked out at what we thought were fireflies. What it turned out to be was that [sappers] had these little pen light flashlights and they flashed them on and off to see the wires. They worked their way through the wires just real quickly flashing, and they saw where the cans were and by the time we realized they were inside... What they had were contact explosives, and they would run from bunker to bunker and just throw them in. We were off the hill, thank God, when it happened. When light came the jets came in and drove the Vietcong off, or I don't know if it was the Vietcong or the Vietnamese army. This is one of those things you sometimes hear about I guess, but there were a lot of them. A lot of the sappers got caught in the wire during the fighting that ensued and never got out and they were just shot to pieces. People went out to the bodies, and just did stuff to them. These were long dead bodies, and [the Marines] would cut them, or stomp the heads or just kick them out of pure hatred and frustration and all kinds of things; because friends had been killed, a lot of Marines had been killed.

We had to bring a guy back from there for dental identification. This crew chief on this helicopter came over to me and said, "Carry him on." I said, "No." And he said, "You're not getting on unless you help carry him on." He was that far gone that they couldn't identify him. He was this hunk, and we put him down in the chopper and he was lying there in the middle with guys on both sides of him and nobody would look at him. He was just this hollow piece of stuff. That was probably the worst.

I remember one great night in Dong Hoi, they showed The Green Berets, the John Wayne Movie. It's hideous; it's a joke. They tried to glamorize Vietnam and make it this great cause. I think the first beer can hit the screen about twenty minutes into it, and then they just tore it down. Nobody could stand it, it was so awful.

I didn't approve of the military tactics. Napalm was getting laid down sometimes, and we'd hear the people scream. Napalm literally sucked the oxygen out of the air, and you would know, they're trapped. I don't think anybody thought, well some people thought that was groovy, but we've certainly learned since. I went to a funeral in Exeter at the Veteran's Cemetery for a man that they knew died from Agent Orange. The Army wouldn't admit it. It was a time when the Army still wasn't admitting it. He came home, thought he was okay. His son suffered some birth defect because of it, I mean, it was just so obvious. The anger at the chapel and the Veteran's Cemetery was just palpable. It was just so hideously unfair. I think somebody should have been hung for that. I don't think we thought about it that way but since then, seeing the consequences, people can't be anything but angry.

Back home I didn't have anybody spit at me. I never knew anybody who did. There was a woman at a cocktail party once, I think it was a friend of my sister, and she came right across the room and she said, "I just heard you were in Vietnam. I can't believe that." So I said, "What can't you believe?" and she said "How many babies did you kill?" That was this huge cliché. This friend of mine had this great answer, "No more than I can eat." It was answering a kind of real stupidity with another kind of stupidity. I just looked at her and said I didn't kill any, or something [like that], and her husband sort of just eased her away and I think he called me later to apologize.

I came into Detroit at like two in the morning, and I remember going home and telling my parents what I had been doing [in Vietnam], and my mother just started crying. We stayed up until five in the morning, and we were never this openly emotional family. Then I went up and took my uniform off and I never put it back on again. I remember thinking about it later and realizing that it wasn't going to mean as much as it should have. It was over now and it wasn't going to mean that much, I had to get on with life, but I wanted it to mean more than it could. Here I had done this thing, I had gone in the Marines and I had gone to Vietnam and I was back in Grosse Pointe. It's funny, I think my father was actually proud that I had done it. He had thought it was crazy to go, but he was proud I had done it. My mother too; she started telling her friends, "Well, you know Bob was in combat."

My parents political views were conservative. They supported Eisenhower and Nixon. It's pretty embarrassing to think about now. There was an incredibly large generation gap between my parents and me. It became well pronounced when I came back from Vietnam. I went way left in my politics. I supported McGovern in 1972. My parents had those rock solid values from the fifties of family and everything else. I was a complete jerk back then, really flaunting that whole freedom thing. I just got hideous, wearing the flowered shirts and bell bottoms, and I wore my old Marine stuff with the long hair. Hindsight is everything, but it seems so fraudulent to me now that we felt it was necessary to shock people by our appearance. At the time it was just this great self-indulgent spree we all went on with drugs and drinking and, we just thought we had it all together, that our parents had been repressed and we were free. It was a crock basically, it really was and the damage is still being felt.

My father, I think, was real disappointed at the way I acted. I was real angry, maybe because we were supposed to be. I just don't think my parents could take in all that happened in the sixties. It was just so overwhelming, I think, for someone of their generation, the World War II generation. I wasn't home a lot, and when I was, there were some uneasy times. I was doing that whole thing they found irresponsible, if not criminal, and I was into it because it was this first time to really cut loose. So, there was this big gap. We came back together eventually, but there were a few years there when it wasn't pretty, it wasn't comfortable at all.

I don't know how much later it was, but I got word that I was receiving a medal. It said you could come down to the armory in uniform and get it at a ceremony or they could just send it to you. My mother said, "Well, we'll all go down and we'll see you get the medal" and I said, "No. I could never put that uniform back on again, I'm just not going to do it." My sister told me later, she said, "That was so shitty, you couldn't put that on and go down there and let her have that moment?" It was just so selfish and stupid and I should have. I should have done that for my mother, but I didn't because I was doing the alienated veteran thing or whatever. I wish I had apologized to her for that, I don't think I ever did.

Looking back, I wouldn't trade [the experience] for anything. Absolutely the best thing I ever did for myself. I don't see it in terms of lending myself to a bankrupt cause or anything like that. It just opened me up to the kind of people I'm never going to see anywhere else. Especially, it served me well in my career as a newspaper columnist. I look at the guys in Grosse Pointe, who went to Michigan or an Ivy League, or graduate school and settled back into Detroit or Grosse Pointe, and still live there, and I think, I've done better than that. I've at least looked at some of the possibilities, I've at least taken one big chance, and I wouldn't trade it for anything. I have never regreted it. I wish I'd been a better Marines than I was, but I was proud. I came out a sergeant and loved it.

The awareness that came out of the sixties was the best thing. Vietnam hopefully taught us something, but I'm not quite sure. The whole idea was we'll never make this mistake again, and I think we can. We see Vietnam now, not in political terms or moral terms, we see it as the great adventure of our generation, and that we're glad we took it, messed up as we may be. The civil rights movement and the awareness of what Blacks had gone through was another positive change in the 60's. The honesty of racial attitudes was good in a way, because as ugly as they were, they were brought out. There was just this incredible division and we have to work on it all the time or it's just going to turn ugly and hurt people again.

People should really question the romantic visions of the sixties. It shouldn't be looked at as this great time that everybody had. I hear some people say, you had the best bands, the best drugs, the best everything. There was incredible turmoil, emotional upheaval, and questioning things that we thought were rock solid for decades. I think the best thing to accept about it is that there is no total resolution of it. Anybody who tells you they have a lock on their feelings, or their views of the impact of the sixties is lying or delusional. The best thing I think is that we can keep learning from it.

| Glossary Words On This Page |

|---|